It may be a clichéd expression, but none of us is able to choose the time and place in which we were born. When asked where we are from, some may reply based on an inherent relationship to where they were born and raised. But these days, we are also free to choose our answer according to other criteria. Some may have a transient connection to place but nevertheless feel this connection to be an important one. With such experiences playing out in different parts of the world, we find ourselves in greater need to imagine other lands and the people living there. The works of writers such as John Maxwell Coetzee, Sijong Kim, and Michiko Ishimure offer a fortunate opportunity for us to broaden our imaginations in such a way. I feel similarly fortunate in being able to view the work of Chikako Yamashiro.

V I D E O

Closer to Poetry than Prose: The Fluidity of Place in the video work of Chikako Yamashiro

Written by Sumitomo Fumihiko

Translated by Sue Hajdu

Chikako Yamashiro,

“Chinbin Western – Representation of the Family”, 2019, video,

©Chikako Yamashiro, courtesy of Yumiko Chiba Associates.

“Chinbin Western – Representation of the Family”, 2019, video,

©Chikako Yamashiro, courtesy of Yumiko Chiba Associates.

In the days before Japan was called Japan, Okinawa was called Okinawa, and Korea was called Korea, how did people imagine other lands? Since the advent of modernity, we have seen dramatic changes in our relationship with the land. These days, we can find out about other locales through the vast amount of media to which we have access, while the highly convenient transportation networks that we previously enjoyed have allowed us to set foot in distant places. However, we only need to consider those fleeing wars and natural disasters to appreciate that not all of this moving around is the result of desire. If anything, we may need to regard the relationship between humans and the land as one that has become tenuous.

Chikako Yamashiro, “Chinbin Western – Representation of the Family”, 2019, video,

©Chikako Yamashiro, courtesy of Yumiko Chiba Associates.

©Chikako Yamashiro, courtesy of Yumiko Chiba Associates.

Yamashiro’s video works contain very little that could be considered descriptive; they are closer to poetry than prose. This allows her viewers to surrender themselves to the flow of images readily. Her works are remarkable for how the images seem to drift in a continuous experience without offering any fixed meaning. Lulled in such a way, viewers may be caught off guard by frequent, sudden changes in pace, and so this characteristic quality of the work may be seen to act in a way that is more subconscious than explicit. In other words, one is enticed to view the works through the senses rather than through the intellect.

Also noteworthy is how this allows Yamashiro to avoid positioning the political issues that have been confronted by many artists from Okinawa — the prefecture in which the artist was born and raised — in between the viewer and the work as existing knowledge. As one might expect, Yamashiro’s work gives considerable weight to Okinawan political issues. But as the work does not offer explanations, viewers may overlook such implications. Even so, the experience of having viewed the work should stimulate the audience to take a good look at similarly structured problems in other parts of the world. Therefore, it is highly appealing that the images, which flow like water at varying tempos, have a sense of plurality, the result of places other than Okinawa being folded into them. Let us take a closer look at some of the works in question.

Also noteworthy is how this allows Yamashiro to avoid positioning the political issues that have been confronted by many artists from Okinawa — the prefecture in which the artist was born and raised — in between the viewer and the work as existing knowledge. As one might expect, Yamashiro’s work gives considerable weight to Okinawan political issues. But as the work does not offer explanations, viewers may overlook such implications. Even so, the experience of having viewed the work should stimulate the audience to take a good look at similarly structured problems in other parts of the world. Therefore, it is highly appealing that the images, which flow like water at varying tempos, have a sense of plurality, the result of places other than Okinawa being folded into them. Let us take a closer look at some of the works in question.

Chikako Yamashiro, “Chinbin Western – Representation of the Family”, 2019,

video, ©Chikako Yamashiro, courtesy of Yumiko Chiba Associates.

The first work I would like to discuss, “A Woman of the Butcher Shop” (2012), can be described as a video installation that explores the desire for flesh. It depicts a street market selling goods, including US military surplus and agricultural products. A large group of male workers wanting to buy food crowds around a woman running a meat stall. Their desire is exposed as more or less like that of an animal. Many viewers are likely to perceive the implications of violence against women in this image of men who work in construction around Okinawa’s US military bases, where sexual violence continues from the war years into the post-war period. In 1995, 85,000 people gathered in a mass rally to protest the assault of a 12-year-old girl by US marines. Of course, this problem is by no means limited to Okinawa; it concerns the history of war and humankind. During the early 1990s, former comfort women of the Imperial Japanese military forces gave testimony, with the Japanese government then acknowledging its involvement. Yamashiro’s representation of areas around US military bases intimates war and sexual violence.

Chikako Yamashiro, “A Woman of the Butcher Shop, 2012 version”,

3-channel video installation, production support from More Museum,

©Chikako Yamashiro, courtesy of Yumiko Chiba Associates.

3-channel video installation, production support from More Museum,

©Chikako Yamashiro, courtesy of Yumiko Chiba Associates.

Meanwhile, the butcher woman in Yamashiro’s video holds a large chunk of meat in her hands. She ecstatically smells it in a gesture where the desire for meat transcends gender differences. If anything, meat appears to be treated as a metaphor for the circulation of different things, rather like the practice of cultural cannibalism espoused by José Oswald de Souza Andrade, in which the other is taken into oneself. In bringing to our awareness such cycles of destruction and creation — in which a living creature is killed, becomes meat, and enters into the body of another living creature — the viewer is given the impression that the complex mechanism of political/economic dependence surrounding the history of military bases and war is absorbed into a larger cycle of culture and nature.

With meat creating such a powerful image, recalling the underwater shots that appear at both the start and end of this video may prove difficult. Shots of women walking in limestone caves like those commonly found in Okinawa are also incorporated into the work. All these contribute to a feeling of layering the body and nature, making the viewer imagine the workings of a primitive spirit or a kind of animism.

With meat creating such a powerful image, recalling the underwater shots that appear at both the start and end of this video may prove difficult. Shots of women walking in limestone caves like those commonly found in Okinawa are also incorporated into the work. All these contribute to a feeling of layering the body and nature, making the viewer imagine the workings of a primitive spirit or a kind of animism.

Chikako Yamashiro, “A Woman of the Butcher Shop, 2012 version”,

3-channel video installation,

production support from More Museum,

©Chikako Yamashiro, courtesy of Yumiko Chiba Associates.

Next, let us move on to “Mud Man” (2016), a video installation in which the sound component and images of groups of people are used to create impressive variations in pace. Covered in mud, people lie on the ground, looking both as if they are dead and in the act of protest. Clumps of mud resembling bird droppings fall from the sky, waking up the sleeping people. They get up and start listening to words that emanate from within them. From the handouts accompanying the artwork, one can infer that these words are those of Japanese and Korean poets, but the viewer cannot take in the meaning of the words, as the video is not subtitled. Rather, one is left with an impression of words that flow out of the mud as a kind of melodic sound.

Next comes a battle scene, its uplifting mood created by the light emanating from fireworks and the vocal percussion of beatboxing. A collage-like way of working with images follows, in which scenes of people crawling forward are superimposed over those of people dancing in clubs. Images of the Battle of Okinawa and the Vietnam War also appear. Video clearly shot from a US military perspective and hip-hop music provide a rich feel for the cultural hybridity of post-war Japan and seem to indicate the ease with which the human body and technology can be redirected to combat.

Next comes a battle scene, its uplifting mood created by the light emanating from fireworks and the vocal percussion of beatboxing. A collage-like way of working with images follows, in which scenes of people crawling forward are superimposed over those of people dancing in clubs. Images of the Battle of Okinawa and the Vietnam War also appear. Video clearly shot from a US military perspective and hip-hop music provide a rich feel for the cultural hybridity of post-war Japan and seem to indicate the ease with which the human body and technology can be redirected to combat.

Chikako Yamashiro, “Mud Man”, 2016 version,

3-channel video installation, made in cooperation with Aichi Triennale 2016,

©Chikako Yamashiro, courtesy of Yumiko Chiba Associates.

3-channel video installation, made in cooperation with Aichi Triennale 2016,

©Chikako Yamashiro, courtesy of Yumiko Chiba Associates.

Scenes from Okinawa, such as its limestone caves, military bases, and the construction sites of Henoko (where land reclamation work is underway to build a new US military base), repeatedly appear in the work. Meanwhile, images from Jeju Island, South Korea, are also mixed into bird’s eye views of fields and hills. The work is edited to make no clear distinction between Jeju and Okinawa. Between the two islands, which are located far from the center of their respective nations, lie histories of violence and voices of resistance.

The words of the poems that flow out of the clumps of mud at the video's opening are experienced as sounds, and it is particularly impressive how this continues, like an echo, right through to the end of the work. We live in a world in which the voices of the past continue to drift in the air. Most certainly, these words are floating around even when we are not viewing the work; it is just that we are not listening.

In contrast to the past, contemporary society lives at a distance from the dead. In “Mud Man”, I feel that the voices of the dead echo here and there in the shots of Okinawa and Jeju Island. This can also be felt strongly in the rather powerful scene at the close of the film depicting the rhythmic clapping of hands, followed by a multitude of limbs stretched upward from a vast field of white lilies. The hands that the many men in “A Woman of the Butcher Shop” stretch toward us are now being stretched upward. Who are these people, whose faces we cannot see, who stretch their hands solely toward the heavens? They look like plants with hands sprouting up from the soil.

The words of the poems that flow out of the clumps of mud at the video's opening are experienced as sounds, and it is particularly impressive how this continues, like an echo, right through to the end of the work. We live in a world in which the voices of the past continue to drift in the air. Most certainly, these words are floating around even when we are not viewing the work; it is just that we are not listening.

In contrast to the past, contemporary society lives at a distance from the dead. In “Mud Man”, I feel that the voices of the dead echo here and there in the shots of Okinawa and Jeju Island. This can also be felt strongly in the rather powerful scene at the close of the film depicting the rhythmic clapping of hands, followed by a multitude of limbs stretched upward from a vast field of white lilies. The hands that the many men in “A Woman of the Butcher Shop” stretch toward us are now being stretched upward. Who are these people, whose faces we cannot see, who stretch their hands solely toward the heavens? They look like plants with hands sprouting up from the soil.

Chikako Yamashiro, “Mud Man”, 2016 version,

3-channel video installation, made in cooperation with Aichi Triennale 2016,

©Chikako Yamashiro, courtesy of Yumiko Chiba Associates.

3-channel video installation, made in cooperation with Aichi Triennale 2016,

©Chikako Yamashiro, courtesy of Yumiko Chiba Associates.

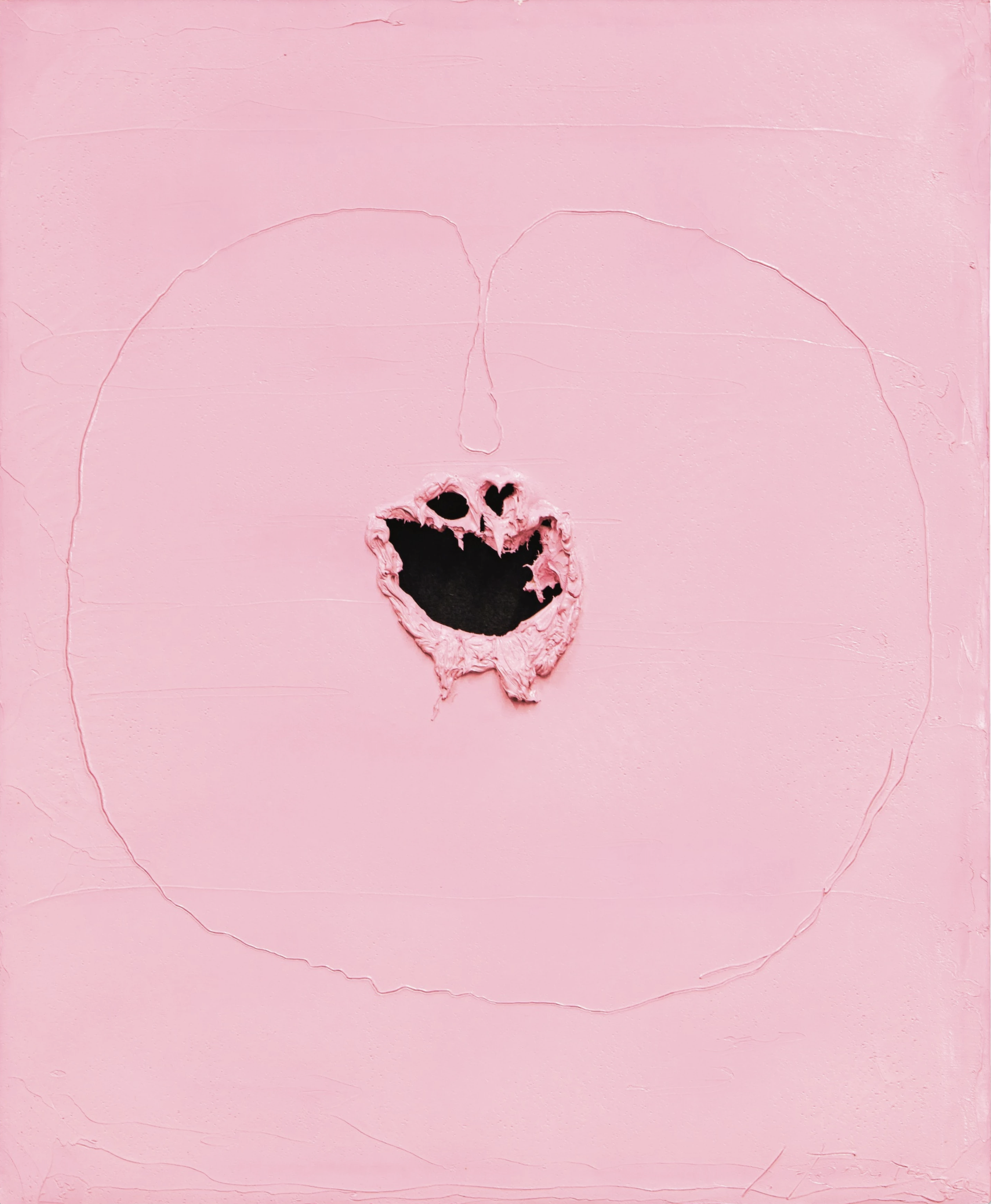

The final work I wish to discuss is “Chinbin Western: Representation of the Family” (2019). Chinbin is an Okinawan sweet, a bit like a crepe. In the manner that the Westerns made in Italy were called ‘Spaghetti Westerns’, this film (which is an opera) was made in Okinawa, hence, “Chinbin Western”. The story unfolds in a dry quarry, a landscape reminiscent of those found in that genre. A man (the husband in one of the two families around which the film revolves) works in the quarry, which mines material for land reclamation in Henoko, where the new US military base is to be built. He makes a show of supporting his seemingly happy family. Despite the children’s anxiety about the discord between their parents, the family manages to maintain its happy-looking veneer. Conversations between family members are sung in the imported culture of opera. This seems to imply that the male-centered ideology that maintains an image of the family for outward appearances is complicit in building the base.

Meanwhile, the film goes on to show the family of a different woman with impressive tattoos and piercings. Her conversations with her grandfather suggest a way of life that tries to be intimate with the history of nature and the land. At the quarry, people dressed in clothing from the time of the Ryukyu Kingdom (1429–1879) perform a play. “Chinbin Western” can be described as a mélange of traditional and imported culture, representations of the contemporary family, and heterogeneous elements.

Meanwhile, the film goes on to show the family of a different woman with impressive tattoos and piercings. Her conversations with her grandfather suggest a way of life that tries to be intimate with the history of nature and the land. At the quarry, people dressed in clothing from the time of the Ryukyu Kingdom (1429–1879) perform a play. “Chinbin Western” can be described as a mélange of traditional and imported culture, representations of the contemporary family, and heterogeneous elements.

Chikako Yamashiro, “Chinbin Western – Representation of the Family”, 2019, video,

©Chikako Yamashiro, courtesy of Yumiko Chiba Associates.

©Chikako Yamashiro, courtesy of Yumiko Chiba Associates.

A feature common to all the works discussed is how the video, which flows in a water-like way at different speeds, can dismantle a dominant story whose existence was once unshakeable through a technique of ‘crossing over’ different content. For example, in “A Woman of the Butcher Shop”, the cycle of destruction and creation that humankind has repeated many times over is superimposed onto the relationship between war and sexual violence. This does not obscure the general idea of the problem. Rather it gives a sense of the deep-rootedness of human desire. In “Mud Man”, war and words concern more than one place. The video’s cultural process of transforming a history of violence into verbal memory and an act of healing is impressive. Meanwhile, “Chinbin Western” dismantles the family's narrative through the contrasting intrusions of tradition and modernity.

Yamashiro’s work is also greatly appealing for how it dismantles dominant narratives and seems to shift them into other cycles. This may be due to the artist’s viewpoint on nature, such as the water or the caves in her work. How human beings in these videos are enveloped in such natural elements and seemingly become one with them is also striking. Political problems that one would have thought to be unique to Okinawa flow out into the cycle of nature. They transcend local issues to form a continuum between Okinawa and other parts of the world.

What I would consider important here is not that such problems will disappear by being integrated into the existence of Mother Nature. Rather, when seen as an extension of unstable human desire and spirit, these problems allow us to feel the close connection between the individual and external society. While having access to a huge amount of information, the individual is also under the firm control of politics and capital. I would argue that an imagination that allows the individual to associate with the external world is needed to expand the depth of our lives and overcome the instability of human desire.

Yamashiro’s work is also greatly appealing for how it dismantles dominant narratives and seems to shift them into other cycles. This may be due to the artist’s viewpoint on nature, such as the water or the caves in her work. How human beings in these videos are enveloped in such natural elements and seemingly become one with them is also striking. Political problems that one would have thought to be unique to Okinawa flow out into the cycle of nature. They transcend local issues to form a continuum between Okinawa and other parts of the world.

What I would consider important here is not that such problems will disappear by being integrated into the existence of Mother Nature. Rather, when seen as an extension of unstable human desire and spirit, these problems allow us to feel the close connection between the individual and external society. While having access to a huge amount of information, the individual is also under the firm control of politics and capital. I would argue that an imagination that allows the individual to associate with the external world is needed to expand the depth of our lives and overcome the instability of human desire.

Chikako Yamashiro, “Mud Man”, 2016 version,

3-channel video installation, made in cooperation with Aichi Triennale 2016,

©Chikako Yamashiro, courtesy of Yumiko Chiba Associates.

3-channel video installation, made in cooperation with Aichi Triennale 2016,

©Chikako Yamashiro, courtesy of Yumiko Chiba Associates.

Luca Bombassei.

Photo credit: ©Jacopo Salvi.

Photo credit: ©Jacopo Salvi.

Luca Bombassei’s journey into collecting does not begin with a single, fixed origin, yet one image lingers in memory—a seemingly simple photograph of architecture set against a snowy backdrop. This early acquisition, minimal yet profound, resonates with a quiet clarity that continues to shape his sensibility as a collector. The dialogue between nature and architecture remains a central thread, weaving through a collection existing at a nexus of time and reflecting Bombassei’s deep engagement with contemporary Italian art and design. From this snowy backdrop, a collection has bloomed, spanning media from sculpture to glass, and unfolding across residences in Venice, Milan, and Salento. In this interview with Nicola Trezzi for ZETTAI, Bombassei reflects on his approach to collecting, the role of intuition in decision-making, and the evolution of his practice over time.

Nicola Trezzi: You come from a family deeply involved in art and culture, and you are an architect and principal of the eponymous, acclaimed firm specializing in the restoration of historical homes. Can you describe the moment in your life when you realized you were a collector and that collecting contemporary art would become a pivotal aspect of both your personal and professional life?

Luca Bombassei: It is difficult to identify a precise moment. I started thirty years ago with photography, perhaps because it is more accessible and immediate for those unfamiliar with collecting. My first purchase was an almost monochromatic landscape—a minimal image of a piece of architecture set against a snowy backdrop. What struck me the most was the dialogue between nature and architecture, a theme I still recognize in myself today. Since then, I’ve realized that collecting is a source of inexhaustible stimulation, both in my private life and profession. Art opens many doors to worlds I had not previously considered or known. This continuous discovery fosters a deep fascination with knowledge—one that grows and, in a certain way, sustains itself. Each new encounter, artist, and gallery offers fresh insights into the field of art, which I deeply cherish and from which new choices continually emerge.

Luca Bombassei: It is difficult to identify a precise moment. I started thirty years ago with photography, perhaps because it is more accessible and immediate for those unfamiliar with collecting. My first purchase was an almost monochromatic landscape—a minimal image of a piece of architecture set against a snowy backdrop. What struck me the most was the dialogue between nature and architecture, a theme I still recognize in myself today. Since then, I’ve realized that collecting is a source of inexhaustible stimulation, both in my private life and profession. Art opens many doors to worlds I had not previously considered or known. This continuous discovery fosters a deep fascination with knowledge—one that grows and, in a certain way, sustains itself. Each new encounter, artist, and gallery offers fresh insights into the field of art, which I deeply cherish and from which new choices continually emerge.

Olivier Mosset, Wallpainting per Gallipoli, 2018.

Polyurethane enamel, 13 x 5 m ca.

Photo credit: ©Andrea Ferrari.

Polyurethane enamel, 13 x 5 m ca.

Photo credit: ©Andrea Ferrari.

NT: Name an artist, an artwork, and an exhibition that have informed the way you look at and collect art.

LB: More than specific names, I would like to highlight an exhibition that was a breakthrough for me and shaped my way of seeing (and collecting) contemporary art: the 1999 Venice Biennale, titled dAPERTutto and curated by Harald Szeemann. It was a particularly important year for the Biennale, as it definitively established the display model by which international exhibitions alongside national pavilions continue to be defined. That year, the Golden Lion Award for Best National Pavilion was given to five female Italian artists: Monica Bonvicini, Luisa Lambri, Bruna Esposito, Paola Pivi, and Grazia Toderi. Over the following years, these artists—undoubtedly among the finest in Italy—have entered my collection, with one or more works by each of them.

LB: More than specific names, I would like to highlight an exhibition that was a breakthrough for me and shaped my way of seeing (and collecting) contemporary art: the 1999 Venice Biennale, titled dAPERTutto and curated by Harald Szeemann. It was a particularly important year for the Biennale, as it definitively established the display model by which international exhibitions alongside national pavilions continue to be defined. That year, the Golden Lion Award for Best National Pavilion was given to five female Italian artists: Monica Bonvicini, Luisa Lambri, Bruna Esposito, Paola Pivi, and Grazia Toderi. Over the following years, these artists—undoubtedly among the finest in Italy—have entered my collection, with one or more works by each of them.

Left to right

On the wall: Roni Horn, Isabelle and Marie, 2005. Two standard C-prints on Fuji Crystal Archive, mounted on 1/8’’ Sintra, 46.99 × 39.34 cm / 48.4 × 40.2 × 2.5 cm each (framed).

Stokke Chair, 1970s.

Monica Bonvicini, Latent Combustion #5, 2015. Chainsaws, black polyurethane (matte finish), chains, hooks, 275 × 130 × 130 cm.

Lucio Fontana, Concetto Spaziale, Attese, 1965. Waterpaint on blue canvas, 65 × 55 cm.

Carlo Scarpa, Easel, 1950–55. Iroko, patinated steel, brass, 261 cm (height).

On the table: Vanessa Beecroft, White Ceramic Head, 2015. Ceramic, 35.5 × 20 × 26.7 cm.

Photo credit: ©Andrea Ferrari.

On the wall: Roni Horn, Isabelle and Marie, 2005. Two standard C-prints on Fuji Crystal Archive, mounted on 1/8’’ Sintra, 46.99 × 39.34 cm / 48.4 × 40.2 × 2.5 cm each (framed).

Stokke Chair, 1970s.

Monica Bonvicini, Latent Combustion #5, 2015. Chainsaws, black polyurethane (matte finish), chains, hooks, 275 × 130 × 130 cm.

Lucio Fontana, Concetto Spaziale, Attese, 1965. Waterpaint on blue canvas, 65 × 55 cm.

Carlo Scarpa, Easel, 1950–55. Iroko, patinated steel, brass, 261 cm (height).

On the table: Vanessa Beecroft, White Ceramic Head, 2015. Ceramic, 35.5 × 20 × 26.7 cm.

Photo credit: ©Andrea Ferrari.

NT: Are you an impulsive buyer or someone who likes to take his time to reflect? Is there a work you regret not having bought?

LB: I am impulsive. Although I admire those who collect in a scientific way, I do so in a more instinctive manner, based on the attraction I feel either toward a given artwork or for the story and experience that the artist wants to communicate.

NT: Do you prefer to buy from Italian galleries or foreign galleries? Do you value an intimate relationship with the people selling art to you, or do you prefer to keep a certain distance?

LB: In line with the variety of works I collect, the places from which I acquire them are quite heterogeneous—from mid-sized Italian galleries and antiquarians, with whom I have developed mutual feelings of affection and appreciation over the years, to more institutional galleries and major auction houses. I do not choose one type of relationship over another a priori; my decisions are guided by the artwork I fall in love with and by whether the circumstances feel right for a purchase.

LB: I am impulsive. Although I admire those who collect in a scientific way, I do so in a more instinctive manner, based on the attraction I feel either toward a given artwork or for the story and experience that the artist wants to communicate.

NT: Do you prefer to buy from Italian galleries or foreign galleries? Do you value an intimate relationship with the people selling art to you, or do you prefer to keep a certain distance?

LB: In line with the variety of works I collect, the places from which I acquire them are quite heterogeneous—from mid-sized Italian galleries and antiquarians, with whom I have developed mutual feelings of affection and appreciation over the years, to more institutional galleries and major auction houses. I do not choose one type of relationship over another a priori; my decisions are guided by the artwork I fall in love with and by whether the circumstances feel right for a purchase.

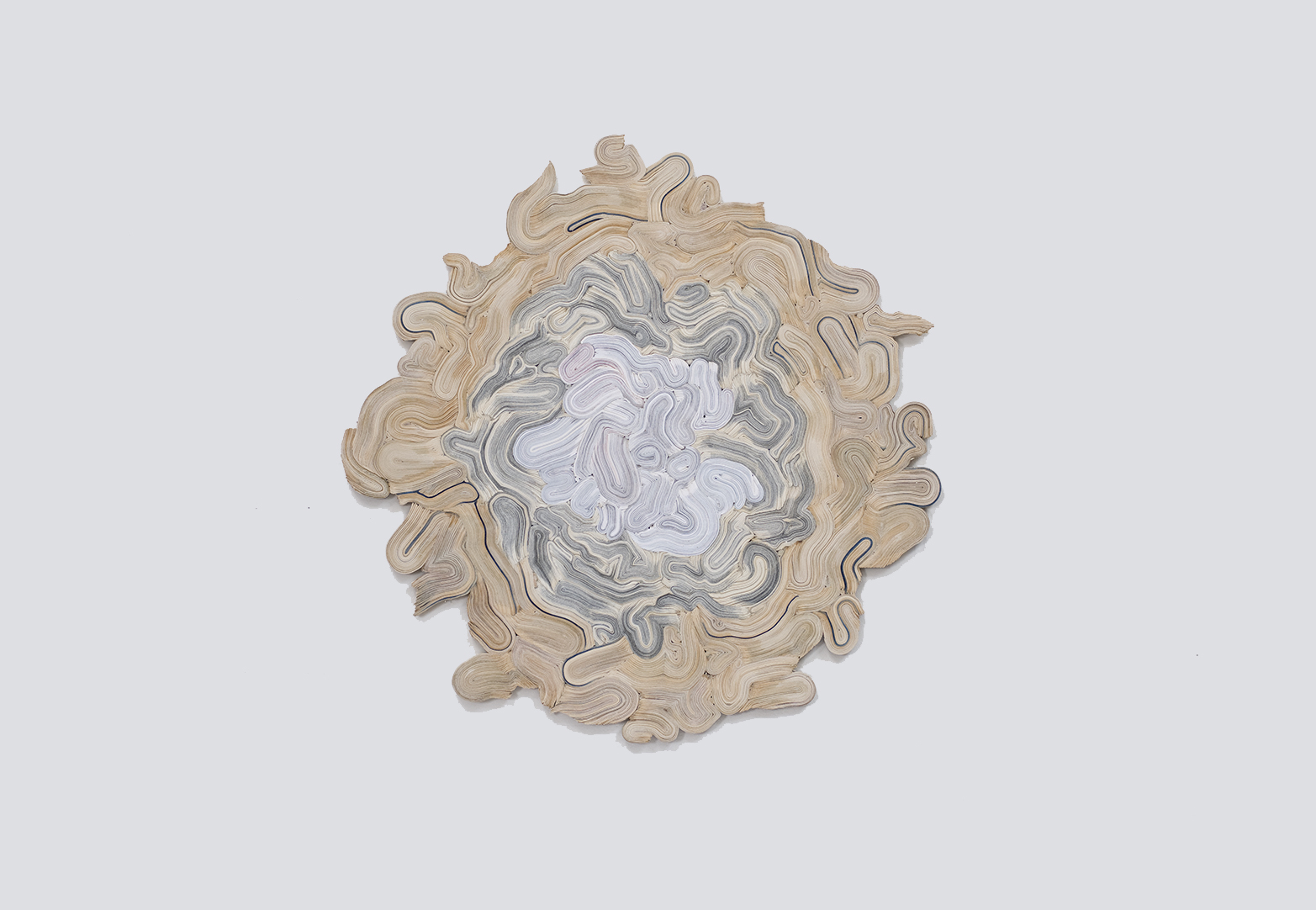

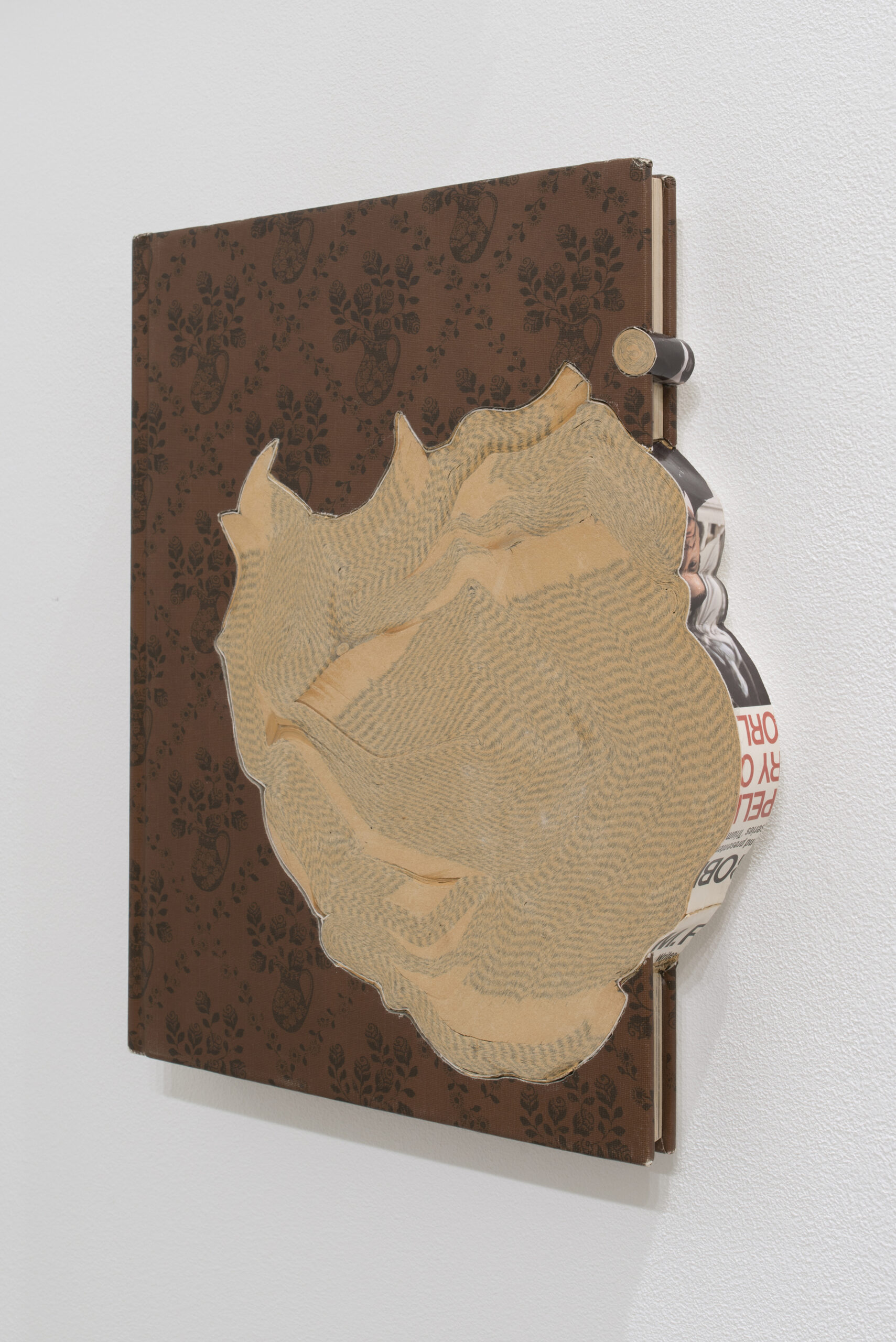

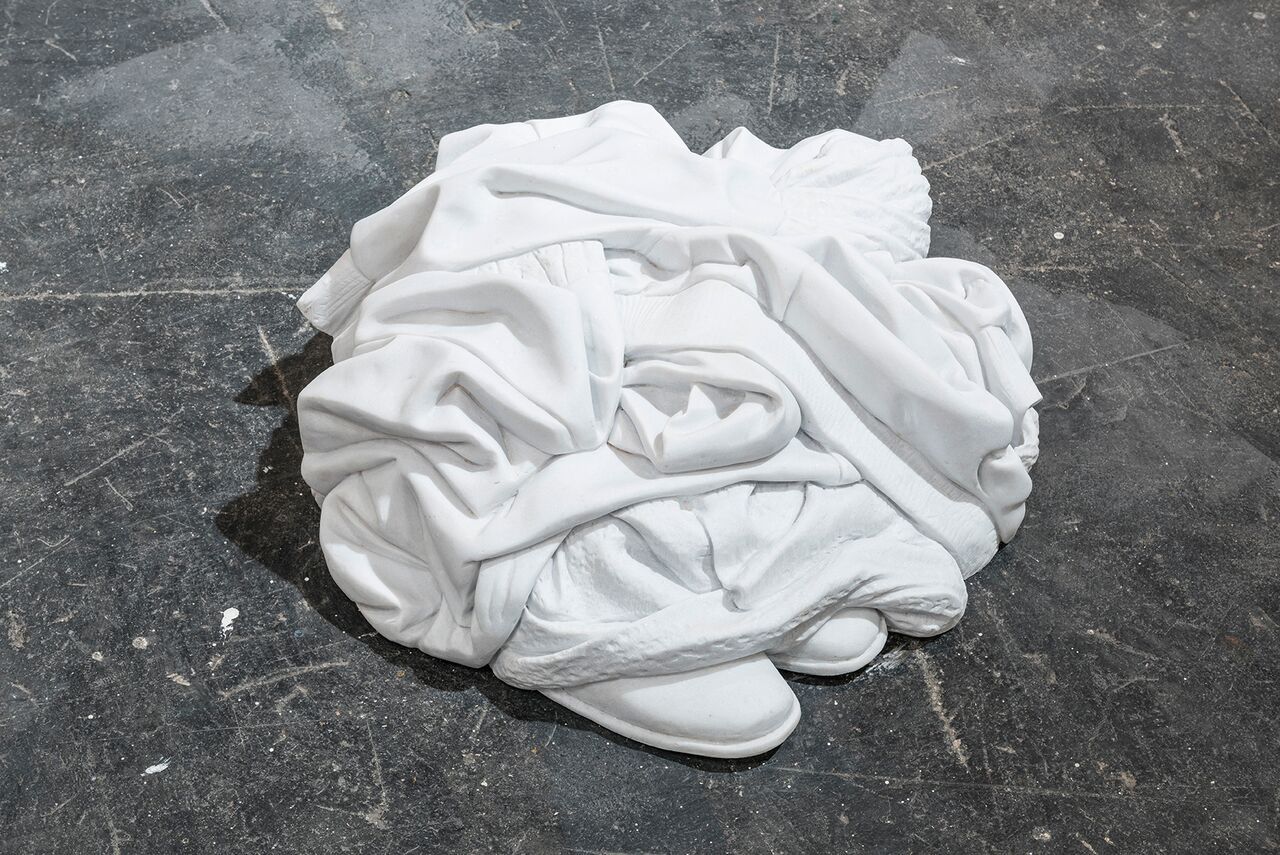

Sol LeWitt, Untitled (from the “Splotches” series),

Black fiberglass,

152.4 × 121.9 × 101.6 cm.

Black fiberglass,

152.4 × 121.9 × 101.6 cm.

NT: While your collection is truly international, you still actively support Italian artists. What do you think makes Italian art unique? Who are the young talents you are currently following, both in Italy and abroad?

LB: As much as it might sound obvious, I believe that Italian art—including the most contemporary—is unique due to the extraordinary artistic and cultural legacy our history carries. This means an inevitable dialogue with the past, being conscious and explicit—such as in Francesco Vezzoli’s reading of classical art—or limited to the artistic education that represents the preliminary stage of the production of new works. If we approach this historical richness with virtuosity, rather than reducing it to a sterile act of recuperation, Italy’s cultural legacy will reveal itself as an irreplaceable resource that ought to be cherished. This dialogue with the future is something that has always guided my decisions, as an architect, collector, and so on.

Regarding young artists, in recent years I have taken an interest in contemporary African art, particularly from countries whose stories have yet to be told and whose voices are still emerging within academic and cultural discourse. Additionally, I have developed a particular interest in female artists—among them Lucia Veronesi, a Mantua-born artist based in Venice, whose recent itinerant project La desinenza estinta (The Extinguished Desinence) I was pleased to support.

LB: As much as it might sound obvious, I believe that Italian art—including the most contemporary—is unique due to the extraordinary artistic and cultural legacy our history carries. This means an inevitable dialogue with the past, being conscious and explicit—such as in Francesco Vezzoli’s reading of classical art—or limited to the artistic education that represents the preliminary stage of the production of new works. If we approach this historical richness with virtuosity, rather than reducing it to a sterile act of recuperation, Italy’s cultural legacy will reveal itself as an irreplaceable resource that ought to be cherished. This dialogue with the future is something that has always guided my decisions, as an architect, collector, and so on.

Regarding young artists, in recent years I have taken an interest in contemporary African art, particularly from countries whose stories have yet to be told and whose voices are still emerging within academic and cultural discourse. Additionally, I have developed a particular interest in female artists—among them Lucia Veronesi, a Mantua-born artist based in Venice, whose recent itinerant project La desinenza estinta (The Extinguished Desinence) I was pleased to support.

Paola Pivi, Why am I so worried?, 2016,

Urethane foam, plastic, feathers, 72 x 221 x 107 cm.

Reproduction from Vanessa Beecroft, Performance VB84, Sala di Niobe, Galleria degli Uffizi, Firenze

Lithographic print, 64 × 44 cm, Arti Grafiche Parini, Torino.

Photo credit: ©Andrea Ferrari.

Urethane foam, plastic, feathers, 72 x 221 x 107 cm.

Reproduction from Vanessa Beecroft, Performance VB84, Sala di Niobe, Galleria degli Uffizi, Firenze

Lithographic print, 64 × 44 cm, Arti Grafiche Parini, Torino.

Photo credit: ©Andrea Ferrari.

NT: Design and architecture are very important to you. Your passion for Memphis is well known, and I was wondering which other designers resonate with you. Do you buy art with a specific design piece in mind, considering how various pieces might complement each other, and so on?

LB: For a few years, alongside my art collection, I have acquired design pieces made of glass. I find glass to be a material that holds particular significance, as it has allowed many designers to engage with and come close to art. In this sense, I see it as the link between two strands of my collecting pursuits—art and design. My collection ranges from Scarpa to Sottsass, following, in some ways, my main point of reference in design, though still oriented toward the production of glass works.

LB: For a few years, alongside my art collection, I have acquired design pieces made of glass. I find glass to be a material that holds particular significance, as it has allowed many designers to engage with and come close to art. In this sense, I see it as the link between two strands of my collecting pursuits—art and design. My collection ranges from Scarpa to Sottsass, following, in some ways, my main point of reference in design, though still oriented toward the production of glass works.

Lucio Fontana, Concetto spaziale, 1966,

Oil on canvas,

73,6 x 60,3 cm.

Photo credit: ©Jacopo Salvi.

Oil on canvas,

73,6 x 60,3 cm.

Photo credit: ©Jacopo Salvi.

NT: As a collector, you pay great attention to how your collection is displayed at home. You divide your time between Milan, Venice, and Salento in Puglia, in the south of Italy—each home is different yet still reflects your personality. Can you associate each home with a different facet of your personality and mention a work of art that encapsulates it?

LB: I would begin with my home in Venice, which best represents the virtuous blend of historicism and contemporaneity so characteristically unique to this city. Among the historical works I have chosen to place there, the most significant is undoubtedly a Capriccio by Canaletto, which happily coexists with pieces by Barbara Kruger and Jenny Holzer, among others. Though seemingly distant, there is a decipherable thread between the ways they engage with society. Just as Canaletto embedded messages of social critique in his works, Kruger and Holzer do the same—only more directly.

In my Milanese apartment, Italian designs from the ’50s and ’60s, like those by Sottsass, are mixed with bold pieces featuring strong colors by Andy Warhol and John Giorno. Finally, in my masseria in Salento, I would highlight a piece by Ibrahim Mahama—a large work created with jute bags that are well integrated into the spacious areas and the original architecture of the house, which I am particularly fond of.

LB: I would begin with my home in Venice, which best represents the virtuous blend of historicism and contemporaneity so characteristically unique to this city. Among the historical works I have chosen to place there, the most significant is undoubtedly a Capriccio by Canaletto, which happily coexists with pieces by Barbara Kruger and Jenny Holzer, among others. Though seemingly distant, there is a decipherable thread between the ways they engage with society. Just as Canaletto embedded messages of social critique in his works, Kruger and Holzer do the same—only more directly.

In my Milanese apartment, Italian designs from the ’50s and ’60s, like those by Sottsass, are mixed with bold pieces featuring strong colors by Andy Warhol and John Giorno. Finally, in my masseria in Salento, I would highlight a piece by Ibrahim Mahama—a large work created with jute bags that are well integrated into the spacious areas and the original architecture of the house, which I am particularly fond of.

Roni Horn, Isabelle and Marie, 2005,

Two standard C-prints on Fuji Crystal Archive,

mounted on 1/8’’ Sintra,

46.99 × 39.34 cm / 48.4 × 40.2 × 2.5 cm.

NT: Speaking of Venice, you have been deeply involved in the city’s cultural scene: you were President of the Venice International Foundation, dedicated to safeguarding its artistic heritage, and you are also involved in the London-based film production company Hoffman, Barney & Foscari. Given all of this, I’m sure the Venice Film Festival is an unmissable event for you—let alone the Venice Biennale! Tell us about your love affair with the city.

LB: Venice has always played a central role in my life, partly due to the Venetian roots of my family. It is a city that inspires love and, for me, an inexhaustible source of inspiration—precisely because of its extraordinary historical heritage and contemporary landscape, especially when considering the future of art and culture. We therefore return to the fundamental idea of reconciling historical legacies with future-oriented visions. Venice not only embodies all of this but also possesses a unique ability to evolve—meaning it can transform and look ahead while remaining loyal to its past, always with an international outlook, always moving forward. My four-year tenure as President of the Venice International Foundation has just ended, and it was an exceptional way to strengthen my connection to the city and highlight the importance of preservation in shaping future cultural decisions. I was pleased to conclude my mandate with the extraordinary exhibition of Francesco Vezzoli in the Scarpa-designed rooms of the Museo Correr.

Through this perspective, the vitality of the Biennale—whether in visual art, cinema, architecture, or dance—serves as a fundamental reality check for me, reinforcing the identity of a city that continuously evolves through an ongoing dialogue between tradition and innovation.

LB: Venice has always played a central role in my life, partly due to the Venetian roots of my family. It is a city that inspires love and, for me, an inexhaustible source of inspiration—precisely because of its extraordinary historical heritage and contemporary landscape, especially when considering the future of art and culture. We therefore return to the fundamental idea of reconciling historical legacies with future-oriented visions. Venice not only embodies all of this but also possesses a unique ability to evolve—meaning it can transform and look ahead while remaining loyal to its past, always with an international outlook, always moving forward. My four-year tenure as President of the Venice International Foundation has just ended, and it was an exceptional way to strengthen my connection to the city and highlight the importance of preservation in shaping future cultural decisions. I was pleased to conclude my mandate with the extraordinary exhibition of Francesco Vezzoli in the Scarpa-designed rooms of the Museo Correr.

Through this perspective, the vitality of the Biennale—whether in visual art, cinema, architecture, or dance—serves as a fundamental reality check for me, reinforcing the identity of a city that continuously evolves through an ongoing dialogue between tradition and innovation.

Francesco Vezzoli, La Musa dell’Archeologia piange, 2021.

Roman Marble Togatus (Circa late 2nd-1st Century), bronze,

140 x 36 x 35 cm.

Photo credit: ©Jacopo Salvi.

NT: Now Milan: Since the 2015 Expo, the city seems to have left its gray and austere reputation behind, emerging as an international European capital whose lively atmosphere attracts not only those drawn to design or fashion week but also those seeking a base to live and work. What makes Milan so unique? Do you think its plurality of voices, its individualism, and its ambition—so perfectly embodied by its constellation of institutions and galleries—are its true strength? And, aside from the much-anticipated museum of contemporary art, what do you think the city still lacks?

LB: Although it is widely criticized today, Milan—like anything that is developing and opening new avenues—remains a city with a certain dynamism and a plethora of opportunities unmatched elsewhere in Italy. The sheer breadth of its cultural offerings, the plurality of voices in its artistic scene, and the social and professional possibilities it fosters make it a city full of promise—one that continues to attract people from both within Italy and abroad.

LB: Although it is widely criticized today, Milan—like anything that is developing and opening new avenues—remains a city with a certain dynamism and a plethora of opportunities unmatched elsewhere in Italy. The sheer breadth of its cultural offerings, the plurality of voices in its artistic scene, and the social and professional possibilities it fosters make it a city full of promise—one that continues to attract people from both within Italy and abroad.

Francesco Vezzoli, Disco Pompidou (Carol Bouquet), 2018. Inkjet print on canvas, metallic embroidery, 68 x 46 cm.

Davina Semo, Glow, 2019. Acrylic mirror, plywood, ball bearings, hardware, stainless steel 184,15 x 123,19 cm.

On the table in the background, couple of marble statuettes.

Photo credit: ©Andrea Ferrari.

NT: My last question to you is about guidance. Your collection is very personal, yet I imagine you rely on the advice of people you trust and appreciate. Who do you turn to? With whom do you have your deepest, most meaningful conversations about art? And, in turn, what kind of advice would you give to a young collector about to embark on this journey—this wonderful adventure—into the world of collecting contemporary art?

LB: Without a doubt, I enjoy exchanging ideas with people I trust and appreciate. I like to listen to their opinions and attend art fairs in their company. There are Italian curators and artists I truly admire, with whom, over the years, I have built special bonds that go beyond mere professional relationships. With them, I also share convivial gatherings, and we converse at length about art and culture. That said, no matter what advice I gratefully and lovingly receive, when it comes to choosing, I follow only my mind—and, above all, my heart.

LB: Without a doubt, I enjoy exchanging ideas with people I trust and appreciate. I like to listen to their opinions and attend art fairs in their company. There are Italian curators and artists I truly admire, with whom, over the years, I have built special bonds that go beyond mere professional relationships. With them, I also share convivial gatherings, and we converse at length about art and culture. That said, no matter what advice I gratefully and lovingly receive, when it comes to choosing, I follow only my mind—and, above all, my heart.

On the wall: John Baldessari, Intersection Series: Woman on bed and man under bed / Beach Scene, 2002. Acrylic and spray paint on photo print, 114.3 × 214.5 cm.

On the table (white marble coffee table by Angelo Mangiarotti):

Fratelli Campana, Prototype Sculpture for Venini.

Enzo Mari, two green glass cubes.

Ettore Sottsass, black ceramic vase, Y29 Yantra Series, Design Centre, 1969.

Photo credit: ©Andrea Ferrari.

Having spent two decades in Germany before returning to Indonesia, Wiyu Wahono brings a global lens to Southeast Asia’s art scene, where he continues to challenge the very nature of collecting. In this interview with Nicola Trezzi for ZETTAI, Wahono delves into his ways of seeing and acquiring art, the allure of works at the intersection between art and technology, and his independence from both the market and institutional systems when it comes to what to buy and where to buy.

Nicola Trezzi: Please describe your collection, including how you would define it, and whether its formation follows a systematic approach or emerges from a more personal, instinctive perspective.

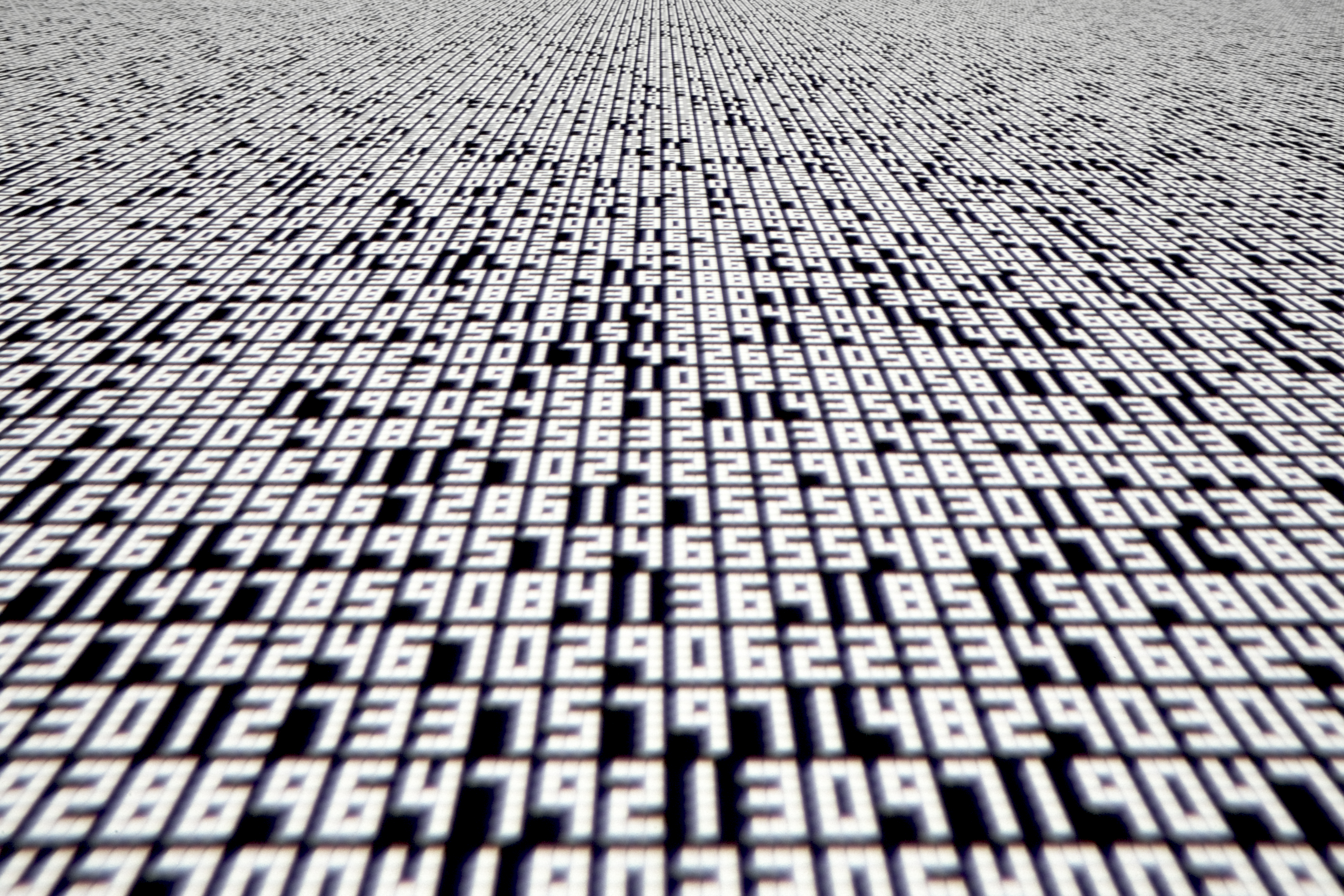

Wiyu Wahono: I follow a simple notion: good artwork reflects the spirit of the time. I ask simple questions: when and why was “contemporary” art born? What was it that annoyed these young artists for them to start acting discursively, to move away from mainstream art? I read a variety of books: Arthur C. Danto, Terry Smith, Julian Stallabrass, and others. And it is in drawing from these cumulative sources of knowledge that I systematically build my contemporary art collection.

Artworks grappling with themes of identity politics, oppression, Western hegemony, urbanization, digitalization, and the environment inform the diverse range of media that I collect: photography, scanography, video art (digital moving image), video mapping, installation, performance art, sound art (pure sound), light art, bio art, robotic art, science and technological art, paintings and sculptures, among others. I also collect immaterial art.

Wiyu Wahono: I follow a simple notion: good artwork reflects the spirit of the time. I ask simple questions: when and why was “contemporary” art born? What was it that annoyed these young artists for them to start acting discursively, to move away from mainstream art? I read a variety of books: Arthur C. Danto, Terry Smith, Julian Stallabrass, and others. And it is in drawing from these cumulative sources of knowledge that I systematically build my contemporary art collection.

Artworks grappling with themes of identity politics, oppression, Western hegemony, urbanization, digitalization, and the environment inform the diverse range of media that I collect: photography, scanography, video art (digital moving image), video mapping, installation, performance art, sound art (pure sound), light art, bio art, robotic art, science and technological art, paintings and sculptures, among others. I also collect immaterial art.

Ryoji Ikeda, data.tron, 2007, audiovisual installation.

Photo credit: Ryuichi Maruo.

Courtesy of Yamaguchi Center for Arts and Media.

Photo credit: Ryuichi Maruo.

Courtesy of Yamaguchi Center for Arts and Media.

NT: You mention works that fall under categories such as video mapping, performance art, sound art, light art, bio art, robotic art, and science and technological art. What challenges do you face as a collector, particularly when it comes to acquiring and maintaining such works?

WW: Collecting such works presents challenges on multiple levels. It starts with understanding the technical specifications required to properly display a piece, such as finding the right multimedia projector to achieve a full, precise image on a wall with predefined dimensions. For an excellent viewing experience, specific projector resolution, brightness (measured in ANSI lumens), throw distance, and lens type are all necessary. Some technological artworks are also temperamental and often difficult to turn on. Computers, for example, don’t always start as expected and may need to be repeatedly shut down and restarted before functioning correctly.

Bio art requires even greater, if not extreme, maintenance, especially when incorporating living organisms. Living Mirror (2013) by Howard Boland and Laura Cinti is an interactive piece consisting of numerous glass flasks filled with liquid and living magnetic bacteria that must be cleaned twice a year. It takes four days for one person to loosen thousands of tiny screws and meticulously wash the insides of all 265 glass flasks.

WW: Collecting such works presents challenges on multiple levels. It starts with understanding the technical specifications required to properly display a piece, such as finding the right multimedia projector to achieve a full, precise image on a wall with predefined dimensions. For an excellent viewing experience, specific projector resolution, brightness (measured in ANSI lumens), throw distance, and lens type are all necessary. Some technological artworks are also temperamental and often difficult to turn on. Computers, for example, don’t always start as expected and may need to be repeatedly shut down and restarted before functioning correctly.

Bio art requires even greater, if not extreme, maintenance, especially when incorporating living organisms. Living Mirror (2013) by Howard Boland and Laura Cinti is an interactive piece consisting of numerous glass flasks filled with liquid and living magnetic bacteria that must be cleaned twice a year. It takes four days for one person to loosen thousands of tiny screws and meticulously wash the insides of all 265 glass flasks.

Ming Wong, Life of Imitation, 2009.

Photo credit: Ming Wong.

Photo credit: Ming Wong.

NT: What was the last artwork you acquired, and what drew you to it?

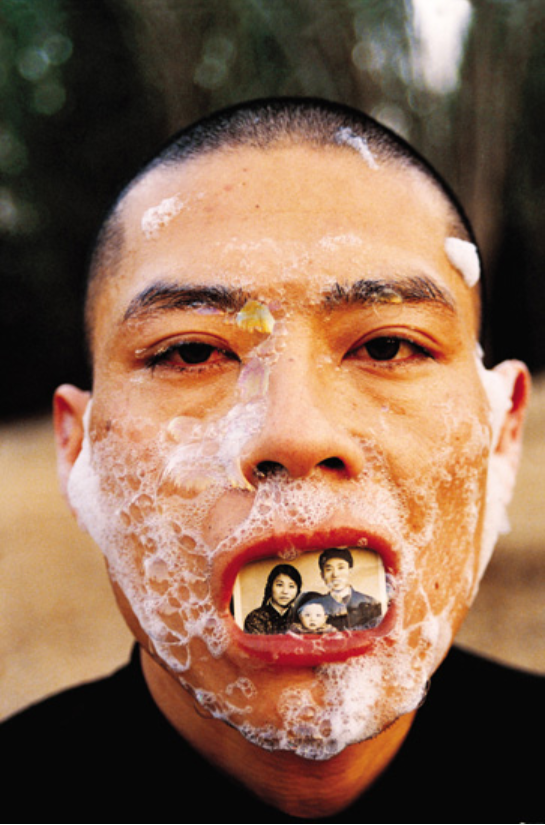

WW: Melati Suryodarmo’s Eins und Eins (2016) had been on my wish list for years before I recently finally decided to acquire it. A powerful performative piece, it unfolds in an entirely white room, where the artist repeatedly pours black ink into her mouth—vomiting, groaning, and embodying a visceral expression of resistance. It is through this act that she echoes Indonesia’s history, where millions have fought against oppression in its many forms.

NT: Do you prefer to acquire artworks from art fairs or galleries, and what informs your choice? Do you also engage with the secondary market?

WW: I began collecting digital art over 17 years ago, at a time when neither commercial galleries nor art fairs embraced the medium—a reality that persists today, with digital art still occupying a marginal space in the market. More recently, my focus has expanded to science and technology-based art, yet these works remain largely overlooked by galleries and fairs. As such, I typically buy artwork directly from artists.

This is not to say, however, that I am opposed to purchasing from galleries, art fairs, or the secondary market. I have acquired works by Zhang Huan and Shirin Neshat through the secondary market, and my purchase of Eins und Eins by Melati Suryodarmo was made through ShanghART.

WW: Melati Suryodarmo’s Eins und Eins (2016) had been on my wish list for years before I recently finally decided to acquire it. A powerful performative piece, it unfolds in an entirely white room, where the artist repeatedly pours black ink into her mouth—vomiting, groaning, and embodying a visceral expression of resistance. It is through this act that she echoes Indonesia’s history, where millions have fought against oppression in its many forms.

NT: Do you prefer to acquire artworks from art fairs or galleries, and what informs your choice? Do you also engage with the secondary market?

WW: I began collecting digital art over 17 years ago, at a time when neither commercial galleries nor art fairs embraced the medium—a reality that persists today, with digital art still occupying a marginal space in the market. More recently, my focus has expanded to science and technology-based art, yet these works remain largely overlooked by galleries and fairs. As such, I typically buy artwork directly from artists.

This is not to say, however, that I am opposed to purchasing from galleries, art fairs, or the secondary market. I have acquired works by Zhang Huan and Shirin Neshat through the secondary market, and my purchase of Eins und Eins by Melati Suryodarmo was made through ShanghART.

Melati Suryodarmo, Eins und Eins, 2016.

Single-channel HD video, stereo sound, 29 minutes 21 seconds.

NT: Do studio visits play a pivotal role in your decision to follow an artist and their work? If so, can you share a studio visit that particularly shaped your perspective as a collector?

WW: I don’t enjoy studio visits, nor do I enjoy being friends with artists. I evaluate artworks based on whether they resonate with and strengthen my existing collection. For me, it’s not about whether the artist has attended a prestigious art school or whether they are destined for “success.” I’m not concerned with their future trajectory or whether they may one day stop creating. If a piece can add depth or coherence to my collection, it becomes part of it.

It also does not matter to me the resale value of the works I acquire. In fact, I consider myself fortunate to have managed to distance myself from the idea of profiting from my collection. The real issue today, in my view, is the growing obsession among collectors with the idea of art as an investment. Too many are driven by the desire for financial gain rather than a genuine passion for the work itself.

WW: I don’t enjoy studio visits, nor do I enjoy being friends with artists. I evaluate artworks based on whether they resonate with and strengthen my existing collection. For me, it’s not about whether the artist has attended a prestigious art school or whether they are destined for “success.” I’m not concerned with their future trajectory or whether they may one day stop creating. If a piece can add depth or coherence to my collection, it becomes part of it.

It also does not matter to me the resale value of the works I acquire. In fact, I consider myself fortunate to have managed to distance myself from the idea of profiting from my collection. The real issue today, in my view, is the growing obsession among collectors with the idea of art as an investment. Too many are driven by the desire for financial gain rather than a genuine passion for the work itself.

Zhang Huan, Foam 13, 1998.

NT: You’ve spent many years living in Europe, and your knowledge of Post-War European and American art is extensive, as well as that of the exhibitions that accompanied said generation of artists. Beyond Harald Szeemann, which curators have inspired and still inspire you, and why?

WW: Okwui Enwezor is very inspiring. The issue of Western hegemony remains a relevant topic today, though I personally think that, most of the time, this issue—along with the need to give balance to underrepresented minorities, in accordance with categories like gender, race, ethnicity, class, and sexuality—often appears in exhibitions in a way that feels quite flat. I don’t believe that simply counting how many women or artists of color are included in exhibitions is enough to spark a meaningful dialogue in art.

I believe curators should develop more sophisticated approaches to enhancing meaningful art production by artists from peripheral positions. One relevant way to do this is by presenting parallel histories, which doesn’t always mean “rewriting history.” For example, bringing a figure like Rasheed Araeen to the forefront.

WW: Okwui Enwezor is very inspiring. The issue of Western hegemony remains a relevant topic today, though I personally think that, most of the time, this issue—along with the need to give balance to underrepresented minorities, in accordance with categories like gender, race, ethnicity, class, and sexuality—often appears in exhibitions in a way that feels quite flat. I don’t believe that simply counting how many women or artists of color are included in exhibitions is enough to spark a meaningful dialogue in art.

I believe curators should develop more sophisticated approaches to enhancing meaningful art production by artists from peripheral positions. One relevant way to do this is by presenting parallel histories, which doesn’t always mean “rewriting history.” For example, bringing a figure like Rasheed Araeen to the forefront.

Deni Ramdani, 0 Degree, 2017.

Soil, water, goldfish.

Soil, water, goldfish.

NT: I would now like to shift the focus to your peers, so to speak: Is there any collector who has inspired or continues to inspire you, and why?

WW: I have read several books about the most prominent art collectors, and at the top of the list is Giuseppe Panza. His ability to acquire works that would later become central pieces in the collections of over ten world-renowned museums, such as the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum in New York and MOCA Los Angeles, is something I find truly extraordinary.

Another collector who stands out is Justin K. Thanhauser, along with his wife, Hilde. Their decision to donate iconic pieces from their collection to the Guggenheim Museum is a perfect example of how a collection can transcend personal ownership to become part of shared cultural heritage. Then there’s Erich Marx, who, through his collection, transformed the Hamburger Bahnhof in Berlin into one of the most important contemporary art spaces in Europe. The German government entrusted him with a former train station to house his collection—an extraordinary gesture that underscores the significance of his vision.

WW: I have read several books about the most prominent art collectors, and at the top of the list is Giuseppe Panza. His ability to acquire works that would later become central pieces in the collections of over ten world-renowned museums, such as the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum in New York and MOCA Los Angeles, is something I find truly extraordinary.

Another collector who stands out is Justin K. Thanhauser, along with his wife, Hilde. Their decision to donate iconic pieces from their collection to the Guggenheim Museum is a perfect example of how a collection can transcend personal ownership to become part of shared cultural heritage. Then there’s Erich Marx, who, through his collection, transformed the Hamburger Bahnhof in Berlin into one of the most important contemporary art spaces in Europe. The German government entrusted him with a former train station to house his collection—an extraordinary gesture that underscores the significance of his vision.

Granular-Synthesis (Kurt Hentschläger and Ulf Langheinrich), Modell 5, 1994.

QT ProRes, 1920 × 1080, 5.1-channel audio installation, 30:00:00.

Photo credit: Bruno Klomfar and Gebhard Sengmüller.

NT: Could you compare the art scenes in Germany, where you lived for many years, and Indonesia, where you reside now? What are the strengths and weaknesses of each, from your perspective?

WW: When I lived in Germany, I wasn’t yet an art collector. While I regularly visited exhibitions for personal enjoyment, I didn’t immerse myself in art theory or the nuances of the art scene at the time. It was more of an appreciation than an intellectual engagement.

However, upon moving to Indonesia and attending exhibitions here, I began to notice a significant shift. The curatorial texts accompanying the exhibitions were often written in a language that felt overly complex, filled with terms that seemed to be more about showcasing the curator's expertise than communicating with a broader audience. As someone who was an art enthusiast but not deeply versed in theory, I found this approach alienating at first.

That said, things have improved over time. There is now a growing generation of young curators in Indonesia who are more approachable and keen on bridging the gap between the art world and the public. They’re moving away from overly academic language and making the art scene more accessible, which is encouraging.

WW: When I lived in Germany, I wasn’t yet an art collector. While I regularly visited exhibitions for personal enjoyment, I didn’t immerse myself in art theory or the nuances of the art scene at the time. It was more of an appreciation than an intellectual engagement.

However, upon moving to Indonesia and attending exhibitions here, I began to notice a significant shift. The curatorial texts accompanying the exhibitions were often written in a language that felt overly complex, filled with terms that seemed to be more about showcasing the curator's expertise than communicating with a broader audience. As someone who was an art enthusiast but not deeply versed in theory, I found this approach alienating at first.

That said, things have improved over time. There is now a growing generation of young curators in Indonesia who are more approachable and keen on bridging the gap between the art world and the public. They’re moving away from overly academic language and making the art scene more accessible, which is encouraging.

Shirin Neshat,

Untitled (from the Soliloquy Series), 1999.

NT: Some would argue that the Indonesian art scene, while full of energy, lacks the infrastructure seen in more established art markets like South Korea or China. Emerging artists are gaining attention, but the scene has not yet reached the level of international prominence that other countries have achieved. What do you believe the scene needs to advance to the next stage, if anything?

WW: Indonesia, with a population of 285 million, is home to a significant number of art collectors. For an emerging artist doing something intriguing, the local market offers relatively accessible opportunities for success. However, this abundance of collectors can also be a double-edged sword. Many young artists, finding immediate recognition and success, sometimes become complacent, leading to work that feels repetitive or lacks depth. The ease of entry into the market has, in some ways, led to a lack of critical self-reflection among emerging creators.

Another pressing issue is the educational gap. Many Indonesian artists, particularly those from the younger generation, aren’t taught how to articulate their concepts effectively, either in their native language or in English. This deficiency limits their ability to engage in deeper, more meaningful dialogues about their work, which in turn hinders their growth on the international stage. To elevate the scene, I believe the government and local institutions should invest in creating programs that help bring internationally recognized art experts to Indonesia in cities like Yogyakarta, Bandung, or Jakarta. These programs would provide valuable opportunities for dialogue, knowledge exchange, and critical feedback, helping to nurture the next generation of artists and curators while fostering a more robust international presence for Indonesian art.

WW: Indonesia, with a population of 285 million, is home to a significant number of art collectors. For an emerging artist doing something intriguing, the local market offers relatively accessible opportunities for success. However, this abundance of collectors can also be a double-edged sword. Many young artists, finding immediate recognition and success, sometimes become complacent, leading to work that feels repetitive or lacks depth. The ease of entry into the market has, in some ways, led to a lack of critical self-reflection among emerging creators.

Another pressing issue is the educational gap. Many Indonesian artists, particularly those from the younger generation, aren’t taught how to articulate their concepts effectively, either in their native language or in English. This deficiency limits their ability to engage in deeper, more meaningful dialogues about their work, which in turn hinders their growth on the international stage. To elevate the scene, I believe the government and local institutions should invest in creating programs that help bring internationally recognized art experts to Indonesia in cities like Yogyakarta, Bandung, or Jakarta. These programs would provide valuable opportunities for dialogue, knowledge exchange, and critical feedback, helping to nurture the next generation of artists and curators while fostering a more robust international presence for Indonesian art.

Teguh Ostenrik, Domus Anguillae (House of Eel), 2022.

Seabed installation in Desa Sembiran, Tejakula, Buleleng, Bali.

Photo credit: Adi Siagian.

NT: You are known for buying difficult works, including videos, installation, and new media. Are you interested in new developments in this path, such as post-internet art or artificial intelligence? If so, which artists do you find most inspiring in this space?

WW: Ryoji Ikeda, Eduardo Kac, Heather Dewey-Hagborg, Pierre Huyghe, Holly Herndon and Mat Dryhurst, Nathan Thompson and Guy Ben-Ary. I think AI is a revolution—one that I expect to have an even greater impact on visual art than the invention of the photographic camera in the 19th century. I started buying AI art five years ago and am still exploring how this bodiless intelligence, with incomplete sense apparatus, no gender, no age, and no private sphere, will redefine artistic and aesthetic boundaries in a non-human realm. As for post-internet art, I’m not familiar with it.

WW: Ryoji Ikeda, Eduardo Kac, Heather Dewey-Hagborg, Pierre Huyghe, Holly Herndon and Mat Dryhurst, Nathan Thompson and Guy Ben-Ary. I think AI is a revolution—one that I expect to have an even greater impact on visual art than the invention of the photographic camera in the 19th century. I started buying AI art five years ago and am still exploring how this bodiless intelligence, with incomplete sense apparatus, no gender, no age, and no private sphere, will redefine artistic and aesthetic boundaries in a non-human realm. As for post-internet art, I’m not familiar with it.

XHABARA, Dawn of the Dajjal, 2021.

MP4 video, 1 min 23 sec.

NT: You once said that you “want to have artworks made of fire, water, smoke, wind, and more.” Did you find them? Considering that Arte Povera is a bit out of reach these days...

WW: Yes, I’ve been fortunate to acquire works that fit this vision. I purchased a sculpture by Indonesian artist Asmujo Irianto depicting a standing man with a burning fire on his head. Another piece by Julian Abraham Togar consists of distilled water (made from the urine of diabetes patients) in glass bottles, placed inside a refrigerator; this was exhibited at the 2018 Sydney Biennale. I also collected a work by Deni Ramdani, which features a transparent plastic bag filled with water and live fish. This piece won the Bandung Contemporary Art Award (BaCAA) in 2017, and as someone who has served as a juror for BaCAA since its inception 13 years ago, it felt particularly significant.

There are also a couple of pieces I’m still eyeing. One is a smoke artwork by Azusa Murakami and Alexander Groves, currently on display at M+ in Hong Kong. I’m also drawn to a wind piece by Ryan Gander that was part of Documenta 13 in 2012. I would love to add both of these to my collection.

NT: If you could go back and advise your younger self on collecting, what kind of advice would you give him?

WW: Reading contemporary art theory books is an act of refining our taste; refined taste gives us the ability to discover the artistic quality of an artwork. Focus on the artistic quality of artworks, as the coherence of an art collection is important. Focus on a few key themes or directions, as it’s simply impossible to collect all the great works available in the market.

WW: Yes, I’ve been fortunate to acquire works that fit this vision. I purchased a sculpture by Indonesian artist Asmujo Irianto depicting a standing man with a burning fire on his head. Another piece by Julian Abraham Togar consists of distilled water (made from the urine of diabetes patients) in glass bottles, placed inside a refrigerator; this was exhibited at the 2018 Sydney Biennale. I also collected a work by Deni Ramdani, which features a transparent plastic bag filled with water and live fish. This piece won the Bandung Contemporary Art Award (BaCAA) in 2017, and as someone who has served as a juror for BaCAA since its inception 13 years ago, it felt particularly significant.

There are also a couple of pieces I’m still eyeing. One is a smoke artwork by Azusa Murakami and Alexander Groves, currently on display at M+ in Hong Kong. I’m also drawn to a wind piece by Ryan Gander that was part of Documenta 13 in 2012. I would love to add both of these to my collection.

NT: If you could go back and advise your younger self on collecting, what kind of advice would you give him?

WW: Reading contemporary art theory books is an act of refining our taste; refined taste gives us the ability to discover the artistic quality of an artwork. Focus on the artistic quality of artworks, as the coherence of an art collection is important. Focus on a few key themes or directions, as it’s simply impossible to collect all the great works available in the market.

Detail from the Art Collection of Irena Popiashvili, Tbilisi, Georgia, 2025.

Photo credit: Guram Kapanadze.

Photo credit: Guram Kapanadze.

From managing a gallery in New York to spearheading transformative projects in Tbilisi, Irena Popiashvili has cultivated spaces for dialogue, growth, and creative experimentation. Through initiatives like VA[A]DS, the Popiashvili Gvaberidze Window Project, and Kunsthalle Tbilisi, Popiashvili continues to nurture new possibilities and expand the landscape of Georgian contemporary art from grassroots to the global stage. Philanthropy is central to her work, as she supports artists by fostering access to new opportunities and contributing to the creation of more cultural infrastructures. Popiashvili’s path, however, has been shaped not by ease but by a vision and deep belief in the power of art to transcend boundaries and transform communities. In the following conversation with Nicola Trezzi for ZETTAI, she reflects on her experiences—past, present, and still in the making.

Nicola Trezzi: We met many years ago... I was then the US editor of Flash Art International, and you ran Newman Popiashvili with Marisa Newman at the time, a progressive gallery in Chelsea. Tell me, how did you enter the field of contemporary art, and what brought you to New York?

Irena Popiashvili: I wrote my bachelor’s thesis at the University of Łódź in Poland. After returning to Georgia, I met a group of Americans and gave them a tour of the museums in Tbilisi. Someone from the tour mentioned that if I wanted to, I could continue my studies in the United States. At the time, there was a significant information gap surrounding contemporary art in the former USSR, with art history textbooks only referencing Picasso’s blue period. Through that chance encounter, I learned about a scholarship opportunity and successfully completed the required tests. This allowed me to pursue my Master’s degree in the United States.

After earning an M.A. in Art History at the University of Georgia in Athens, I took additional classes at Emory University in Atlanta, where my professor was James Meyer. I wrote my thesis on Andy Warhol’s “Death and Disaster” series, and my primary motivation for coming to the U.S. was to immerse myself in contemporary art. James Meyer encouraged me to move to New York—though I didn’t know anyone there at the time—but he assured me that I could find a job in an art gallery. He even connected me with Andrew Solomon, a friend of his whose book on the Russian avant-garde had just been published.

Following his advice, I moved from Atlanta to New York. Chassie Post Gallery, which I had worked with in Atlanta, opened a space in New York, and I secured a part-time job there. I also interned at various galleries, including Frederieke Taylor and several uptown galleries. Within a year, I became a gallery director at Joyce Goldstein Gallery on Wooster Street, right next to the Drawing Center. That’s how it all began.

Irena Popiashvili: I wrote my bachelor’s thesis at the University of Łódź in Poland. After returning to Georgia, I met a group of Americans and gave them a tour of the museums in Tbilisi. Someone from the tour mentioned that if I wanted to, I could continue my studies in the United States. At the time, there was a significant information gap surrounding contemporary art in the former USSR, with art history textbooks only referencing Picasso’s blue period. Through that chance encounter, I learned about a scholarship opportunity and successfully completed the required tests. This allowed me to pursue my Master’s degree in the United States.

After earning an M.A. in Art History at the University of Georgia in Athens, I took additional classes at Emory University in Atlanta, where my professor was James Meyer. I wrote my thesis on Andy Warhol’s “Death and Disaster” series, and my primary motivation for coming to the U.S. was to immerse myself in contemporary art. James Meyer encouraged me to move to New York—though I didn’t know anyone there at the time—but he assured me that I could find a job in an art gallery. He even connected me with Andrew Solomon, a friend of his whose book on the Russian avant-garde had just been published.

Following his advice, I moved from Atlanta to New York. Chassie Post Gallery, which I had worked with in Atlanta, opened a space in New York, and I secured a part-time job there. I also interned at various galleries, including Frederieke Taylor and several uptown galleries. Within a year, I became a gallery director at Joyce Goldstein Gallery on Wooster Street, right next to the Drawing Center. That’s how it all began.

Irena Popiashvili, founder of VA[A]DS (Visual Art, Architecture, and Design School) at the Free University of Tbilisi, Georgia, 2014.

Photo credit: Davit Giorgadze.

Photo credit: Davit Giorgadze.

NT: You were among the first to exhibit the work of Slavs and Tatars, who I also interviewed for ZETTAI. How deeply has their practice influenced your way of looking at art and culture?

IP: I discovered Slavs and Tatars at the New York Print Fair in 2008. They were not known at all back then. The fair was at the old Dia Art Foundation building on 22nd Street, and I was going up the stairs to the fair when I saw a poster, Men are from Murmansk, Women are from Vilnius, hanging on the stairway. The references made to the former USSR cities made me laugh. I was humored, curious, and decidedly went to look for the Slavs and Tatars stand, where I met Payam [Sharifi] and Kasia [Korczak]. I invited them to visit me at the gallery, and we opened their first New York solo exhibition in 2009, “A Thirteenth Month Against Time.”

It was great. MoMA bought their work and offered them a solo exhibition. I collaborated with them again in 2023 for a Kunsthalle Tbilisi exhibition alongside Giorgi Khaniashvili at Atinati’s Cultural Center.

IP: I discovered Slavs and Tatars at the New York Print Fair in 2008. They were not known at all back then. The fair was at the old Dia Art Foundation building on 22nd Street, and I was going up the stairs to the fair when I saw a poster, Men are from Murmansk, Women are from Vilnius, hanging on the stairway. The references made to the former USSR cities made me laugh. I was humored, curious, and decidedly went to look for the Slavs and Tatars stand, where I met Payam [Sharifi] and Kasia [Korczak]. I invited them to visit me at the gallery, and we opened their first New York solo exhibition in 2009, “A Thirteenth Month Against Time.”

It was great. MoMA bought their work and offered them a solo exhibition. I collaborated with them again in 2023 for a Kunsthalle Tbilisi exhibition alongside Giorgi Khaniashvili at Atinati’s Cultural Center.

Koka Ramishvili,

Mtatsminda, 2021,

Digital print, ED 1/4 2 AP,

76 x 100 cm.

Photo credit: Guram Kapanadze.

Digital print, ED 1/4 2 AP,

76 x 100 cm.

Photo credit: Guram Kapanadze.

NT: After spending time in New York, you then returned to Georgia. You transitioned from the commercial sector—although your gallery was very experimental and intellectual—to the academic world. Can you tell us about your adventure in this field?

IP: Marisa Newman and I have organized some great exhibitions that I am very proud of. We presented the first two solo exhibitions of Raul de Nieves, and the first New York solo exhibitions of Basim Magdy, Jorge Peris, and Alberto Tadiello. But, moving back to Georgia in 2012 was a significant change, both culturally and academically. I was appointed rector of the Tbilisi State Academy of Arts, becoming the first woman in the institution’s nearly 100-year history to hold the position, and the second, after the founder, who was not an artist. Although my tenure at the Academy was brief, I had gained valuable insight into navigating that world by the time I was invited by the founder of the Free University of Tbilisi to establish a new art school: VA[A]DS, the Visual Arts and Design School.

IP: Marisa Newman and I have organized some great exhibitions that I am very proud of. We presented the first two solo exhibitions of Raul de Nieves, and the first New York solo exhibitions of Basim Magdy, Jorge Peris, and Alberto Tadiello. But, moving back to Georgia in 2012 was a significant change, both culturally and academically. I was appointed rector of the Tbilisi State Academy of Arts, becoming the first woman in the institution’s nearly 100-year history to hold the position, and the second, after the founder, who was not an artist. Although my tenure at the Academy was brief, I had gained valuable insight into navigating that world by the time I was invited by the founder of the Free University of Tbilisi to establish a new art school: VA[A]DS, the Visual Arts and Design School.

Giorgi Khaniashvili, Family Portrait, 2007,

Mud, glue on cardboard,

120 x 100 cm.

Photo credit: Guram Kapanadze.

NT: I am actually interested in knowing how you navigate the academic field and its restrictions, especially after being independent for so long.

IP: My move was partly due to personal reasons, but driven by a desire to improve the arts education in Georgia. The same year, I was curating an exhibition at the National Gallery in Tbilisi called “Reframing the 80s,” an exhibition on Georgian art from the end of the ’80s to the beginning of the ’90s. While working on the show, I was still living in New York and would travel to Georgia for research and to locate artwork from that period. As much as I wanted the exhibition to have an impact on the public, it became clear to me that education was the only thing capable of creating change in how contemporary art was publicly perceived. However, the education system that I encountered in Georgia was obsolete and completely out of touch with reality.

The VA[A]DS school at the Free University is now nearly ten years old. I collaborated with the university’s administrative team and a talented group of professionals in Tbilisi to design the initial program. Over the years, the curriculum has been continuously adjusted and improved, evolving based on my experiences with students and visiting professors. I am fortunate to have worked with the best artists and designers at the school, and I have had creative freedom from the university regarding the selection of instructors. In a way, I am curating the educators who guide the new generation of Georgian artists and designers. Additionally, the architecture program, created by my colleague Jesse Vogler, who relocated from the U.S. to Georgia, has become a very successful and integral part of the school.

IP: My move was partly due to personal reasons, but driven by a desire to improve the arts education in Georgia. The same year, I was curating an exhibition at the National Gallery in Tbilisi called “Reframing the 80s,” an exhibition on Georgian art from the end of the ’80s to the beginning of the ’90s. While working on the show, I was still living in New York and would travel to Georgia for research and to locate artwork from that period. As much as I wanted the exhibition to have an impact on the public, it became clear to me that education was the only thing capable of creating change in how contemporary art was publicly perceived. However, the education system that I encountered in Georgia was obsolete and completely out of touch with reality.

The VA[A]DS school at the Free University is now nearly ten years old. I collaborated with the university’s administrative team and a talented group of professionals in Tbilisi to design the initial program. Over the years, the curriculum has been continuously adjusted and improved, evolving based on my experiences with students and visiting professors. I am fortunate to have worked with the best artists and designers at the school, and I have had creative freedom from the university regarding the selection of instructors. In a way, I am curating the educators who guide the new generation of Georgian artists and designers. Additionally, the architecture program, created by my colleague Jesse Vogler, who relocated from the U.S. to Georgia, has become a very successful and integral part of the school.

Sabine Hornig; Layout for a Sculpture 2, 2023.

Pigment Print and handprinted Silkscreen on Archival Paper; 56 x 56 cm; Edition of 10 + 3 AP - this is AP 1/10.

© Sabine Hornig and VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn Germany.