Nicola Trezzi: Let’s start with your entrance to the world of contemporary art and to collecting. Can you talk about the idea of “rebirth,” a term you use to define the current moment?

Galila Barzilaï-Hollander: I never considered myself a collector because I don’t like the word “collecting.” It sounds very materialistic and possessive, and is often related to social status. Nevertheless, the only alternative is “artoholic”; it sounds like a sickness, but it’s better than calling myself a collector. It is a sort of compulsive, emotional need more than an act of deciding to belong to a group of people. It is something very personal.

Nicola Trezzi: You’ve mentioned the idea of being ‘born again’—could you articulate what that means to you personally? Are you referring to a spiritual transformation, a pivotal life event, or a shift in perspective? I’d love to understand more about the context and significance behind that expression.

GBH: I’ve always considered my experience with contemporary art as a form of rebirth. Through discovering contemporary art, I discovered myself. That was 20 years ago—which is why, today, I say that I am 20 years old. It’s a simple way to reclaim years of life.

This rebirth was a process of becoming aware of someone within me I hadn’t known before—uncovering another dimension of my personality, my existence, and ultimately, who I am. All of that was redefined through art.

C O L L E C T O R S

Following

The Red Thread

An Interview with Galila Barzilaï-Hollander

Written by Nicola Trezzi

Portrait of Galila at Galila’s P.O.C. (Brussels, BE), 2022.

Photo credit: Damon de Backer.

Photo credit: Damon de Backer.

Galila Barzilaï-Hollander takes an unorthodox approach to collecting. She never set out to become a “collector”—in fact, the very label makes her bristle. What began in 2005 as a spontaneous, emotional response to the loss of her husband has since flourished into Galila’s P.O.C (Passion, Obsession, Collection), a dedicated space housed in a renovated 1950s industrial building in Brussels, created in collaboration with architect Bruno Corbusier. Her collection is driven not by status or strategy, but by instinct, personal symbolism, and the sheer joy of discovery. From eyes and chairs, to books, cigarettes, and interfaith, the various themes in her collection are deeply intimate yet universally resonant—born from grief, shaped by curiosity, and guided by the eye rather than the art market. In this interview with Nicola Trezzi for ZETTAI, she offers a glimpse into the motivations, methods, and sensibilities behind her ever-evolving practice.

Exhibition view, Works on Paper–Galila’s Collection,

Jewish Museum of Belgium (Brussels, BE), 2021–2022.

Photo credit: Jewish Museum of Belgium.

Jewish Museum of Belgium (Brussels, BE), 2021–2022.

Photo credit: Jewish Museum of Belgium.

NT: The collection is remarkably vast and diverse, yet there are some points where common elements emerge. Could you speak to any underlying themes, motifs, or intentions that connect these works across such a broad spectrum?

GBH: This is only natural, because there is a red thread running through all the works, which is, obviously, me. I chose them, probably by a subconscious or unconscious guideline, in dialogue with various aspects of my life, my philosophy of life, my vision of life, my own truth. It’s a sort of self-portrait.

NT: Can you tell me about the moment you first decided to share your collection with others? What prompted that decision, and what did it mean to you to make something so personal and publicly accessible?

GBH: Sharing the collection with others was not an intellectual decision or an intention; it was the consequence of a sudden awareness that came from people visiting the exhibitions curated from my collection by third parties—not my initiative—who gave me very special, emotional feedback. They felt connected to the art world in a way that they did not feel when seeing a museum exhibition. It was also a sort of “positive voyeurism,” as if they were intruding into my life and getting to know me better through my selection of art. A playful situation—like a ping pong between me, my works, and themselves—where sometimes they see me, sometimes they see the work and the reason why I chose it, and sometimes they gain a better idea of who I am, an interpretation of who I am. There is a lot of thinking and feeling involved.

GBH: This is only natural, because there is a red thread running through all the works, which is, obviously, me. I chose them, probably by a subconscious or unconscious guideline, in dialogue with various aspects of my life, my philosophy of life, my vision of life, my own truth. It’s a sort of self-portrait.

NT: Can you tell me about the moment you first decided to share your collection with others? What prompted that decision, and what did it mean to you to make something so personal and publicly accessible?

GBH: Sharing the collection with others was not an intellectual decision or an intention; it was the consequence of a sudden awareness that came from people visiting the exhibitions curated from my collection by third parties—not my initiative—who gave me very special, emotional feedback. They felt connected to the art world in a way that they did not feel when seeing a museum exhibition. It was also a sort of “positive voyeurism,” as if they were intruding into my life and getting to know me better through my selection of art. A playful situation—like a ping pong between me, my works, and themselves—where sometimes they see me, sometimes they see the work and the reason why I chose it, and sometimes they gain a better idea of who I am, an interpretation of who I am. There is a lot of thinking and feeling involved.

Nobuyoshi Araki, Colorscapes, 1991.

Courtesy Galila’s Collection Belgium.

Photo credit: Nobuyoshi Araki.

NT: From there you started P.O.C—can you talk about this space you opened and about the rules you give to yourself?

GBH: P.O.C stands for Passion, Obsession, Collection. That is already a summary— three ingredients of a cocktail which define what I do and who I am.

NT: It is an explosive cocktail, a bomb!

GBH: It’s an overdose of P, an overdose of O, an overdose of C, so it’s a sickness in a way, as I said. I didn’t decide to collect; it was not a plan. But once I got into it, it became a way to share. And when I see people leaving P.O.C, they have this feeling that something deeply profound just happened to them—a realization of freedom, letting go, being natural, being individualistic in a good way, not hiding behind a mask, not being what people expect you to be without feeling bad about it. People regularly express the same feelings in different ways. They feel relieved that they can be themselves if they respect the other. This is a form of self-respect. It is also about opening up to others.

GBH: P.O.C stands for Passion, Obsession, Collection. That is already a summary— three ingredients of a cocktail which define what I do and who I am.

NT: It is an explosive cocktail, a bomb!

GBH: It’s an overdose of P, an overdose of O, an overdose of C, so it’s a sickness in a way, as I said. I didn’t decide to collect; it was not a plan. But once I got into it, it became a way to share. And when I see people leaving P.O.C, they have this feeling that something deeply profound just happened to them—a realization of freedom, letting go, being natural, being individualistic in a good way, not hiding behind a mask, not being what people expect you to be without feeling bad about it. People regularly express the same feelings in different ways. They feel relieved that they can be themselves if they respect the other. This is a form of self-respect. It is also about opening up to others.

View of Galila’s P.O.C., Brussels, 2022.

Photo credit: Damon De Backer.

Photo credit: Damon De Backer.

NT: Do you think this emotional response people have is a direct result of being in a space surrounded by these artworks? What is it about the environment—or perhaps the energy of the collection itself—that you feel contributes to this experience?

GBH: You have here a harmonic variety of artworks, artists, techniques, and interpretations, which makes people feel they can be themselves while respecting and accepting differences; it has a real, non-verbal impact on people. I even think that, for some people, this experience is a sort of rebirth as well. I’ve seen people, mostly women, who were on the verge of crying from emotions. They felt happy, relieved… as if they had received a massage, an authorization.

NT: We spoke about the collection and the ways you associate works in very personal ways, but sometimes there are associations that we can also see and are visible to others. Could you speak about some of those?

GBH: The association might be obvious, like a theme—chairs, books—but many times, there are works that are farther apart from each other—different techniques, languages, messages—and yet, one feels a sense of harmony and connection. In my mental universe, this means that it is a message about living together; we can all have our own specificities, and yet we can still share, communicate, understand, and compromise, if necessary, without tension or conflict. That, in itself, is already a program. Society could be like that, and we would then have a beautiful world.

GBH: You have here a harmonic variety of artworks, artists, techniques, and interpretations, which makes people feel they can be themselves while respecting and accepting differences; it has a real, non-verbal impact on people. I even think that, for some people, this experience is a sort of rebirth as well. I’ve seen people, mostly women, who were on the verge of crying from emotions. They felt happy, relieved… as if they had received a massage, an authorization.

NT: We spoke about the collection and the ways you associate works in very personal ways, but sometimes there are associations that we can also see and are visible to others. Could you speak about some of those?

GBH: The association might be obvious, like a theme—chairs, books—but many times, there are works that are farther apart from each other—different techniques, languages, messages—and yet, one feels a sense of harmony and connection. In my mental universe, this means that it is a message about living together; we can all have our own specificities, and yet we can still share, communicate, understand, and compromise, if necessary, without tension or conflict. That, in itself, is already a program. Society could be like that, and we would then have a beautiful world.

Lin Zhipeng, Coco's Melon Face, 2018.

Courtesy Galila’s Collection, Belgium.

Photo: Lin Zhipeng.

NT: Can you define what is exceptional and outstanding? What makes objects enter your space? I am trying to avoid words you might not like!

GBH: I’m not looking for anything, I don’t search—I find. I make discoveries, and I usually describe the way I operate as driven by instinct, looking without seeing and seeing without looking. I have the impression that my eyes can register things that, before going to my brain, go to my stomach. Gut feeling!

So, I don’t have an explanation for why this or that is good, or why I’m attracted to it. Sometimes I only realize much later that there was a connection with something else I own, or that it was meaningful “because of something”; but that first reaction is very pure, non-intellectual, and basic, almost animalistic. I choose things that are good for me. I’m not a scholar, so I don’t put a lot of words around it. Maybe it is not good for other people, but in my context, it satisfies my sensitivity.

GBH: I’m not looking for anything, I don’t search—I find. I make discoveries, and I usually describe the way I operate as driven by instinct, looking without seeing and seeing without looking. I have the impression that my eyes can register things that, before going to my brain, go to my stomach. Gut feeling!

So, I don’t have an explanation for why this or that is good, or why I’m attracted to it. Sometimes I only realize much later that there was a connection with something else I own, or that it was meaningful “because of something”; but that first reaction is very pure, non-intellectual, and basic, almost animalistic. I choose things that are good for me. I’m not a scholar, so I don’t put a lot of words around it. Maybe it is not good for other people, but in my context, it satisfies my sensitivity.

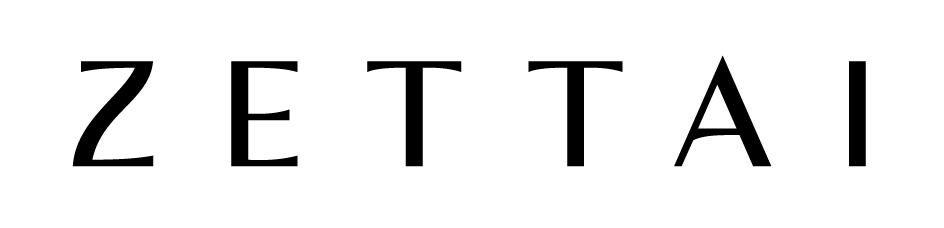

Marlon de Azambuja, Metaesquema, 2008.

Courtesy Galila’s Collection, Belgium.

Photo: Marlon de Azambuja.

NT: Can you define what is exceptional and outstanding? What makes objects enter your space? I am trying to avoid words you might not like!

GBH: I’m not looking for anything, I don’t search—I find. I make discoveries, and I usually describe the way I operate as driven by instinct, looking without seeing and seeing without looking. I have the impression that my eyes can register things that, before going to my brain, go to my stomach. Gut feeling!

So, I don’t have an explanation for why this or that is good, or why I’m attracted to it. Sometimes I only realize much later that there was a connection with something else I own, or that it was meaningful “because of something”; but that first reaction is very pure, non-intellectual, and basic, almost animalistic. I choose things that are good for me. I’m not a scholar, so I don’t put a lot of words around it. Maybe it is not good for other people, but in my context, it satisfies my sensitivity.

GBH: I’m not looking for anything, I don’t search—I find. I make discoveries, and I usually describe the way I operate as driven by instinct, looking without seeing and seeing without looking. I have the impression that my eyes can register things that, before going to my brain, go to my stomach. Gut feeling!

So, I don’t have an explanation for why this or that is good, or why I’m attracted to it. Sometimes I only realize much later that there was a connection with something else I own, or that it was meaningful “because of something”; but that first reaction is very pure, non-intellectual, and basic, almost animalistic. I choose things that are good for me. I’m not a scholar, so I don’t put a lot of words around it. Maybe it is not good for other people, but in my context, it satisfies my sensitivity.

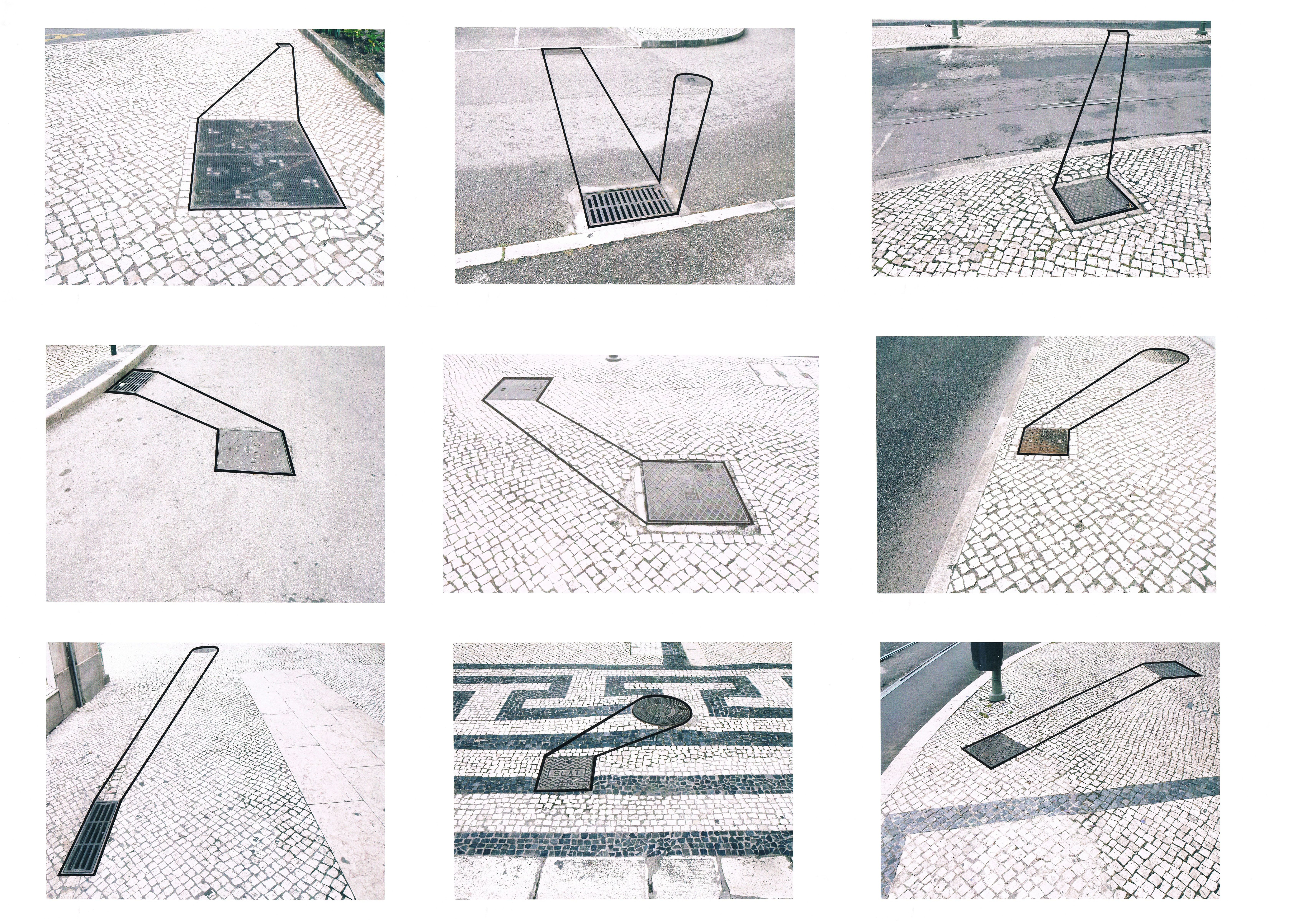

Anna Maria Maiolino, Untitled (from the Vida Afora series - Photopoemaction), 1981.

Courtesy Galila’s Collection Belgium.

Photo credit: Anna Maria Maiolino.

NT: You mentioned there is a rule at P.O.C, your space in Brussels, that you always add. Could you tell me more about this rule? What inspired it, and how do you see it shaping the experience or atmosphere of the space?

GBH: The title of the exhibition is “Overdose,” and I chose it for very practical reasons: I didn’t want to have a theme, nor did I want to limit myself to something with borders, so there is no limit, just like in an overdose. I can add, and add, and add… It is quite fascinating to see that although additional works are regularly added and the space becomes more and more crowded, people don’t leave with the impression of an “overdose,” as if it is too much to digest or too much for the eyes or the brain. They always say, “I am going to come back again.” There is a natural awareness of how much one can truly absorb at first sight or on a first visit, but it never feels heavy. People feel light because, despite there being so much to take in, there is humor accompanying serious matters—a sort of de-dramatization of things. Nothing feels heavy, and maybe this is what people are looking for, or maybe what they need: something that gives them oxygen.

GBH: The title of the exhibition is “Overdose,” and I chose it for very practical reasons: I didn’t want to have a theme, nor did I want to limit myself to something with borders, so there is no limit, just like in an overdose. I can add, and add, and add… It is quite fascinating to see that although additional works are regularly added and the space becomes more and more crowded, people don’t leave with the impression of an “overdose,” as if it is too much to digest or too much for the eyes or the brain. They always say, “I am going to come back again.” There is a natural awareness of how much one can truly absorb at first sight or on a first visit, but it never feels heavy. People feel light because, despite there being so much to take in, there is humor accompanying serious matters—a sort of de-dramatization of things. Nothing feels heavy, and maybe this is what people are looking for, or maybe what they need: something that gives them oxygen.

View of Galila’s P.O.C., Brussels, 2022.

Photo credit: Damon De Backer.

Photo credit: Damon De Backer.

NT: Do you think that it is difficult to have this lightness in museums?

GBH: I don’t think it is difficult. I think museum scholars might need some “therapy.” As proof, when I had my exhibition at the Holon Design Museum, many visitors to the exhibition spontaneously exclaimed, “This should go to MoMA!” The message is that people feel good about it, and I don’t understand why museums are not doing something similar. I don’t think I’m going “down to the people” per se. I think that, through the way art is presented here, we bring people up. They don’t feel like they are out of context or that they don’t belong. It is a very interesting phenomenon, where even people who have nothing to do with contemporary art or art at all don’t feel intimidated; on the contrary, they feel a sense of belonging with it, that they understand and can give their own interpretations without fear of criticism or being ridiculed. They see that it is natural to look and understand.

I don’t explain the works when I give tours at P.O.C; I just let people look, feel whatever they feel, and think whatever they think; it is not a school with “good” answers or “bad” answers. I myself sometimes offer an interpretation of a work different from what the artist intended; I tell the artist, “This is my interpretation,” and sometimes it happens that the artist replies, “I actually prefer your interpretation.” This is not mathematics! There is no single truth.

GBH: I don’t think it is difficult. I think museum scholars might need some “therapy.” As proof, when I had my exhibition at the Holon Design Museum, many visitors to the exhibition spontaneously exclaimed, “This should go to MoMA!” The message is that people feel good about it, and I don’t understand why museums are not doing something similar. I don’t think I’m going “down to the people” per se. I think that, through the way art is presented here, we bring people up. They don’t feel like they are out of context or that they don’t belong. It is a very interesting phenomenon, where even people who have nothing to do with contemporary art or art at all don’t feel intimidated; on the contrary, they feel a sense of belonging with it, that they understand and can give their own interpretations without fear of criticism or being ridiculed. They see that it is natural to look and understand.

I don’t explain the works when I give tours at P.O.C; I just let people look, feel whatever they feel, and think whatever they think; it is not a school with “good” answers or “bad” answers. I myself sometimes offer an interpretation of a work different from what the artist intended; I tell the artist, “This is my interpretation,” and sometimes it happens that the artist replies, “I actually prefer your interpretation.” This is not mathematics! There is no single truth.

Galila’s hand.

Photo credit: Damon de Backer.

NT: At P.O.C, your collection notably avoids displaying the names of artists alongside the works. How do you think this choice affects the way visitors experience the art, and what message do you hope it conveys about identity and authorship?

GBH: The lack of names is something that makes people feel much more comfortable. When you see many names and you don’t recognize any, you might feel ashamed, as if you are out of place. Without names, you are free to let go of any feelings and judge for yourself. And astonishingly, without exception, all of the artists represented in P.O.C liked the idea of having no hierarchy, with no one being disregarded or overly considered.

NT: P.O.C includes a section dedicated to religion and coexistence. Could you share what inspired this focus?

GBH: I’m not religious. I have my own bible. I have my own ten commandments about how to be a good person in society. So, I don’t stick to any religion. I look at religion as a way of expressing the belief that there should be a desire to share, to know and understand each other, and to create a better world—basically, to reach peace.

GBH: The lack of names is something that makes people feel much more comfortable. When you see many names and you don’t recognize any, you might feel ashamed, as if you are out of place. Without names, you are free to let go of any feelings and judge for yourself. And astonishingly, without exception, all of the artists represented in P.O.C liked the idea of having no hierarchy, with no one being disregarded or overly considered.

NT: P.O.C includes a section dedicated to religion and coexistence. Could you share what inspired this focus?

GBH: I’m not religious. I have my own bible. I have my own ten commandments about how to be a good person in society. So, I don’t stick to any religion. I look at religion as a way of expressing the belief that there should be a desire to share, to know and understand each other, and to create a better world—basically, to reach peace.

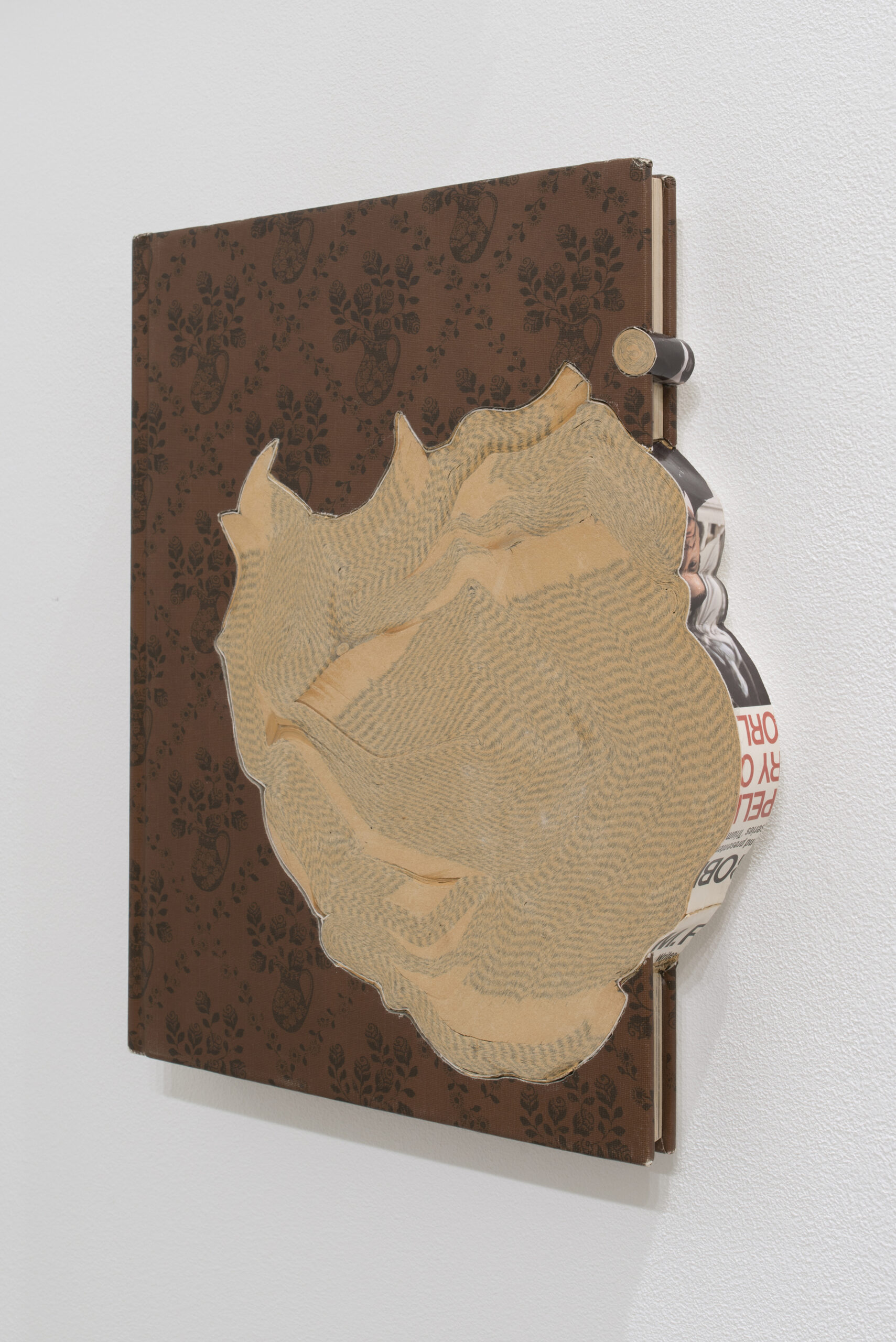

Jonathan Callan,

Art around Mythology around Global Strategy, 2014.

Courtesy Galila’s Collection Belgium.

Photo credit: Jonathan Callan.

Jonathan Callan,

Pith, 2006.

Courtesy Galila’s Collection Belgium.

Photo credit: Nik Suk.

Jonathan Callan,

The Pelican History of the World in Flower Arranging, 2015.

Courtesy Galila’s Collection Belgium.

Photo credit: Isabelle Arthuis.

NT: Do you feel that art holds a transformative power? If so, how do you see that transformation happening—whether on an individual, community, or societal level?

GBH: Art is something that works on your subconscious and has a role in that sense. Art carries a great transformative power by challenging perspectives, evoking deep emotion, and inspiring change—within both individuals as well as across societies. It bridges gaps between cultures, communicates the unspeakable, and definitively awakens deeper understandings of our human experience.

NT: Do you think that your approach to collecting and presenting art is a blend of deliberate planning and spontaneous intuition? How do these two aspects interact in your process, and can you give examples of when something unexpected shaped the collection or the presentation?

GBH: Nothing is ever planned. Art is the best glue one can ever have between people in society. It is a universal language that can touch anyone regardless of religion, age, or origin. It unites people.

The best example I can give is from the visits of groups at P.O.C. There are two types of groups: the first is a pre-constituted group of people who already know each other, typically belonging to the same social status. The second is a group of individuals who register separately online for a time slot, not knowing each other and often coming from different social and professional environments. Surprisingly, it is in this latter group where I discover much stronger interactions between participants. It is the miracle of the connection that unites strangers who might have nothing in common, and yet connect through art in a very short time, sharing their thoughts, emotions, impressions, and ideas. For me, that is the power of art!

GBH: Art is something that works on your subconscious and has a role in that sense. Art carries a great transformative power by challenging perspectives, evoking deep emotion, and inspiring change—within both individuals as well as across societies. It bridges gaps between cultures, communicates the unspeakable, and definitively awakens deeper understandings of our human experience.

NT: Do you think that your approach to collecting and presenting art is a blend of deliberate planning and spontaneous intuition? How do these two aspects interact in your process, and can you give examples of when something unexpected shaped the collection or the presentation?

GBH: Nothing is ever planned. Art is the best glue one can ever have between people in society. It is a universal language that can touch anyone regardless of religion, age, or origin. It unites people.

The best example I can give is from the visits of groups at P.O.C. There are two types of groups: the first is a pre-constituted group of people who already know each other, typically belonging to the same social status. The second is a group of individuals who register separately online for a time slot, not knowing each other and often coming from different social and professional environments. Surprisingly, it is in this latter group where I discover much stronger interactions between participants. It is the miracle of the connection that unites strangers who might have nothing in common, and yet connect through art in a very short time, sharing their thoughts, emotions, impressions, and ideas. For me, that is the power of art!

Exhibition view, L’art de Rien, Centrale for Contemporary Art (Brussels, BE), 2023-2024.

Photo credit: Philippe De Gobert.

Photo credit: Philippe De Gobert.

NT: Do you personally give tours to the groups? If so, how do you guide their experience—do you share insights, encourage interaction, or let them explore freely? How does the process usually work?

GBH: While giving my tour, I usually tell them the “story” of my life—how I started getting involved in art, the impact it had on me, and how I choose to live. The art world became a big family to me. Age-wise, most of my artists could be my own kids. I feel lucky to have such warm relationships with most of them that are built on sharing, trust, deep respect, and a kind of love. All of this contributed to my rebirth.

NT: When you reflect on the past, present, and future of P.O.C, what stands out most to you? How do you see its evolution so far, and what do you imagine or hope for its role and impact moving forward?

GBH: To be very frank, the present and the past are very linked, since for me it is a considerably short time. As for the future: this is a very complicated and serious issue; I receive more and more feedback from different sources—visitors, people involved in education, the medical world—expressing the opinion that this place should remain a “human adventure,” something very different from a museum. It has its own specific criteria of art, excellency, and purpose. I would love to find a solution to make this last and continue on as my contribution to society.

GBH: While giving my tour, I usually tell them the “story” of my life—how I started getting involved in art, the impact it had on me, and how I choose to live. The art world became a big family to me. Age-wise, most of my artists could be my own kids. I feel lucky to have such warm relationships with most of them that are built on sharing, trust, deep respect, and a kind of love. All of this contributed to my rebirth.

NT: When you reflect on the past, present, and future of P.O.C, what stands out most to you? How do you see its evolution so far, and what do you imagine or hope for its role and impact moving forward?

GBH: To be very frank, the present and the past are very linked, since for me it is a considerably short time. As for the future: this is a very complicated and serious issue; I receive more and more feedback from different sources—visitors, people involved in education, the medical world—expressing the opinion that this place should remain a “human adventure,” something very different from a museum. It has its own specific criteria of art, excellency, and purpose. I would love to find a solution to make this last and continue on as my contribution to society.

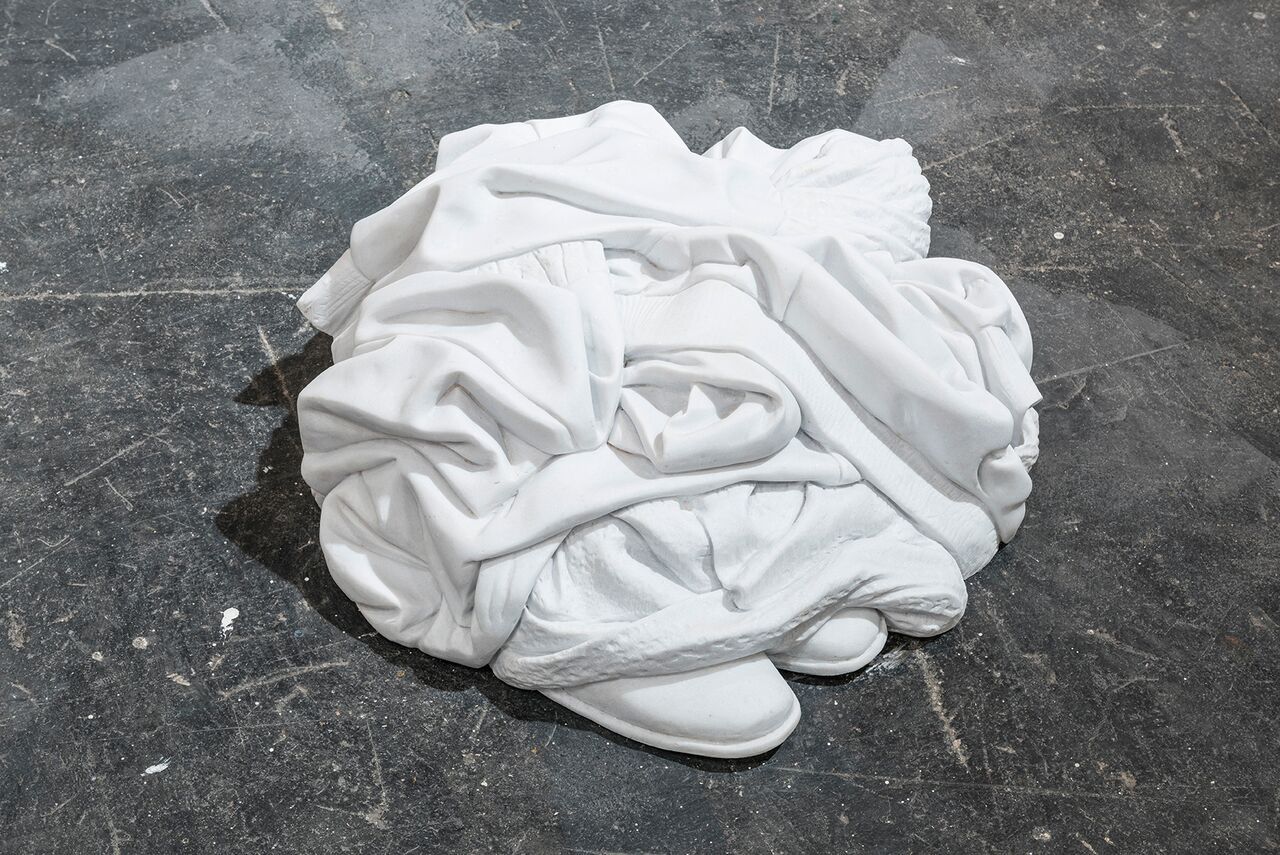

A Kassen, Pile of Clothes, 2016.

Courtesy Galila’s Collection Belgium.

Photo credit: A Kassen.

NT: Can you elaborate on what you mean by that? I’d love to understand more about your perspective and the ideas behind it.

GBH: Maybe I should consider a donation—not for my name, but for the well-being of society. Saying “for humanity” would sound a little pretentious. This connection has, from my experience up to the present moment, a profound impact on visitors. Beyond its tremendous psychological and emotional impacts, it also triggers the creative mind. It is a key to problem-solving that enables people to explore with a full 360° vision and, finally, brings attention to the many social and human issues of today and tomorrow.

NT: Do you believe that art carries a certain degree of mystery?

GBH: I wouldn’t use the word “mystery.” Art is a powerful tool that you cannot define. It is so vast. I’m a very intuitive person, so I often react in a visceral way without intellectualizing the whole thing. I just feel things, and I’m not afraid to accept what I feel. It’s like the song by Frank Sinatra: “I do it my way.”

GBH: Maybe I should consider a donation—not for my name, but for the well-being of society. Saying “for humanity” would sound a little pretentious. This connection has, from my experience up to the present moment, a profound impact on visitors. Beyond its tremendous psychological and emotional impacts, it also triggers the creative mind. It is a key to problem-solving that enables people to explore with a full 360° vision and, finally, brings attention to the many social and human issues of today and tomorrow.

NT: Do you believe that art carries a certain degree of mystery?

GBH: I wouldn’t use the word “mystery.” Art is a powerful tool that you cannot define. It is so vast. I’m a very intuitive person, so I often react in a visceral way without intellectualizing the whole thing. I just feel things, and I’m not afraid to accept what I feel. It’s like the song by Frank Sinatra: “I do it my way.”

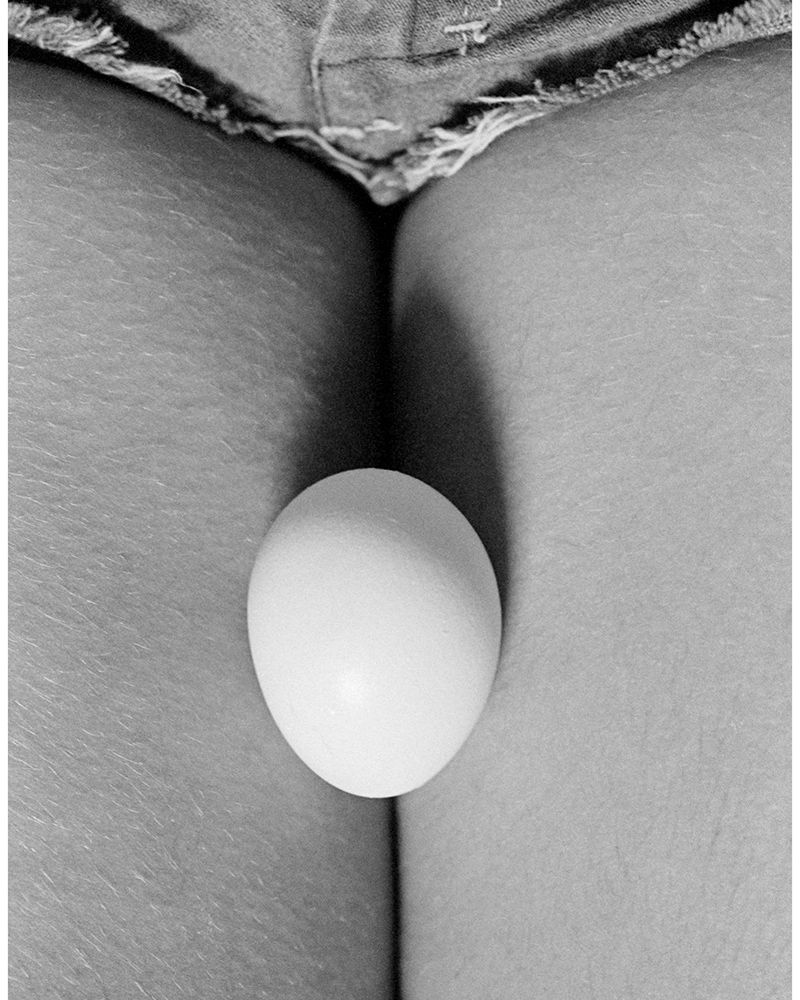

lulia Bucureşteanu, Domestic mythologies, 2023.

Courtesy Galila’s Collection Belgium.

Photo credit: Sybren Dallinga.

Courtesy Galila’s Collection Belgium.

Photo credit: Sybren Dallinga.