Nicola Trezzi: You are based in Mexico City but you originally established Tercerunquinto in Monterrey. Can you share the premises of your collaboration and, considering the urban focus of your work, how much the city of Monterrey influenced the early stage of your practice?

Tercerunquinto: We have always felt that being born and growing up in Monterrey has played a major part in shaping on our ideas about art. The influence of the city is clearly evident when you look at the materials we began to work with. Monterrey is a very important industrial city; cement, concrete and other materials related to construction have been the touchstones of progress and social development and are thus emblematic of Monterrey’s culture. On the other hand, the collective, which we formed when we were still art students, was for us a survival strategy in an environment which was very hostile towards the younger artistic community. Monterrey – its institutions and support system – was not particularly benevolent to artists, unless you were useful to their ideas; and as young people training to become artists we were much more limited in terms of access.

M I X E D M E D I A

Institutional Negotiations

An Interview with Tercerunquinto

Written by Nicola Trezzi

Tercerunquinto, “Dismantling and Relocation of the National Emblem”, 2008.

Photo documentation of the action on the facade of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs’ former building, Mexico City.

Courtesy of the artists and Proyectos Monclova, Mexico City.

Simultaneously ephemeral and monumental, the work of Tercerunquinto intervenes in both public and private spaces, questioning the limits between the two spheres, and breaking down the components of these systems. Deeply rooted in the context of Mexico and yet inextricably connected to global instances, both in terms of language, issues and positions, the practice of Tercerunquinto could be seen as a perfect mix between a sociological research team, an architectural firm, and a collective of artists. In this interview with Nicola Trezzi, the members of Tercerunquinto openly share their position on how blending art and politics can actually generate a “space for negotiation” that, if it won’t change the world, will definitely change the mindset of those who inhabit it.

Installation view of the group exhibition "Normal Expectations: Contemporary Art in Mexico", Museo Jumex, Mexico City, Mexico, 2018.

Photo credit: Ramiro Chaves.

Photo credit: Ramiro Chaves.

NT: Tell us about your name, what are the literal and conceptual meanings of the Spanish word Tercerunquinto and how did you come upon such a name? Did the name influence your practice or vice versa? Did your ideas create the name or was it working together in a specific way that brought you to use this word as a signature?

Tercerunquinto: Basically, the name directs one to think of an integer or a whole divided into several parts, although only one of them is named: the 3rd out of 5. For us, the name was a way to recognize ourselves as a collective, as part of a dynamic entity that was never totally complete and in which the involvement of each of its members changed with each work. Even later, when the contributions of other agents outside Tercerunquinto were integrated, we realized that the name had further connotations, since the work was extended and completed with the intervention of other people who are not artists. The name can be seen as a way to define collectivity.

![]()

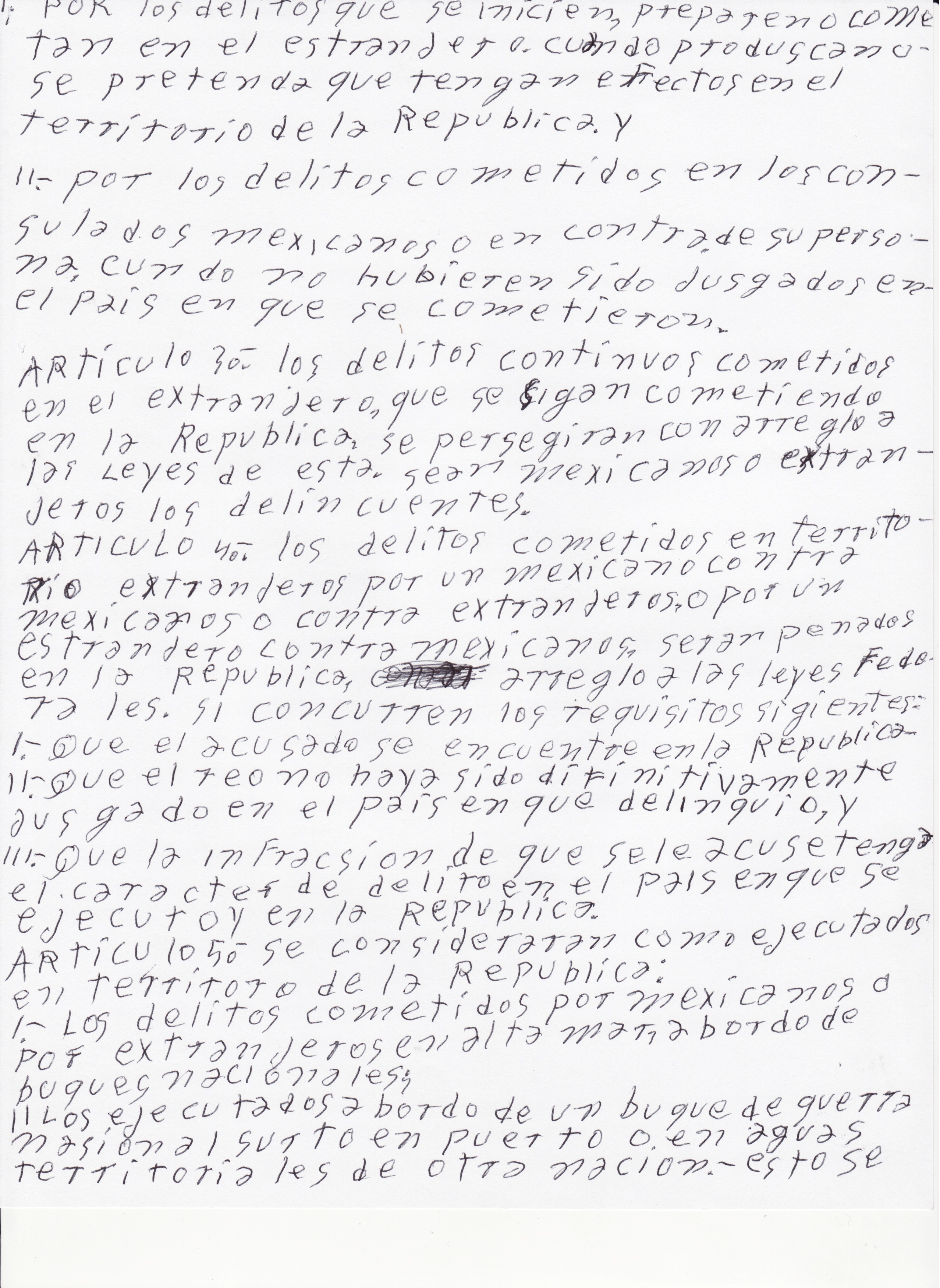

Installation view of “Staircase”, 2002. From the series Dwelling Houses.

Reinstalled for "Tercerunquinto: Obra Inconclusa", Museo / Fundación Amparo, Puebla, Mexico, 2018.

cur. Cuauhtémoc Medina and Taiyana Pimentel.

Courtesy of the artists and Proyectos Monclova, Mexico City.

Tercerunquinto: Basically, the name directs one to think of an integer or a whole divided into several parts, although only one of them is named: the 3rd out of 5. For us, the name was a way to recognize ourselves as a collective, as part of a dynamic entity that was never totally complete and in which the involvement of each of its members changed with each work. Even later, when the contributions of other agents outside Tercerunquinto were integrated, we realized that the name had further connotations, since the work was extended and completed with the intervention of other people who are not artists. The name can be seen as a way to define collectivity.

Installation view of “Staircase”, 2002. From the series Dwelling Houses.

Reinstalled for "Tercerunquinto: Obra Inconclusa", Museo / Fundación Amparo, Puebla, Mexico, 2018.

cur. Cuauhtémoc Medina and Taiyana Pimentel.

Courtesy of the artists and Proyectos Monclova, Mexico City.

NT: What was your most radical project to date, in terms of scale, ambition, complexity and realization? If you could do it again, what would you change?

Tercerunquinto: It is difficult to answer this question because, although it is true that we have made ambitious and complex works, some of them quite large, none of them has had giant proportions. Another approach is to define the magnitude of these works not necessarily in terms of their physical aspects, but rather through their conceptual scope. The first three works that we produced consisted of a series of modest walls of regular size, arranged in different situations according to the inner space in which they were presented. We later became aware of the fact that these walls projected a direction outwards, towards the public space. Such a realization generated new experiences and ideas in relation to our task as artists. We thought that the expressive capacities of the construction materials (mortar and concrete blocks) always had to be employed through interventions that were trespassing the logical and functional arrangements of various spaces. This was at the beginning, when we wanted to address our context or even try to define it and, to answer your question, at the time those were very ambitious concerns and interests, at least for us.

Public sculpture in the urban periphery of Monterrey (2003-2006) was probably the first work that put us, since we first had the idea, in a very different and much more complex horizon from that of the previous works. This work forced us to review and discuss historical concepts related to art; to produce new work dynamics, such as exploring geographical areas of the city in order to have a map of the type of contexts we were interested in, and to collaborate with powerful agents to obtain the economic resources needed to produce the piece. Subsequently, when our work gain institutional acceptance, the concept of negotiation not only became pivotal, it also moved to a higher level, so to speak, since it often involved authorities and power structures outside the field of art; for instance our contribution to group exhibition Mexico: Sensitive Negotiations curated by Taiyana Pimentel in 2002 required negotiating permission to tear down the walls of an office of the Consulate General of Mexico in Miami – where the exhibition took place – with the Mexican Minister of Foreign Affairs. As to what we would change, it is very difficult to answer to that; perhaps we probably have a fairly healthy relationship with our past, we try not to punish ourselves for our mistakes or whatever we could have done differently.

Tercerunquinto: It is difficult to answer this question because, although it is true that we have made ambitious and complex works, some of them quite large, none of them has had giant proportions. Another approach is to define the magnitude of these works not necessarily in terms of their physical aspects, but rather through their conceptual scope. The first three works that we produced consisted of a series of modest walls of regular size, arranged in different situations according to the inner space in which they were presented. We later became aware of the fact that these walls projected a direction outwards, towards the public space. Such a realization generated new experiences and ideas in relation to our task as artists. We thought that the expressive capacities of the construction materials (mortar and concrete blocks) always had to be employed through interventions that were trespassing the logical and functional arrangements of various spaces. This was at the beginning, when we wanted to address our context or even try to define it and, to answer your question, at the time those were very ambitious concerns and interests, at least for us.

Public sculpture in the urban periphery of Monterrey (2003-2006) was probably the first work that put us, since we first had the idea, in a very different and much more complex horizon from that of the previous works. This work forced us to review and discuss historical concepts related to art; to produce new work dynamics, such as exploring geographical areas of the city in order to have a map of the type of contexts we were interested in, and to collaborate with powerful agents to obtain the economic resources needed to produce the piece. Subsequently, when our work gain institutional acceptance, the concept of negotiation not only became pivotal, it also moved to a higher level, so to speak, since it often involved authorities and power structures outside the field of art; for instance our contribution to group exhibition Mexico: Sensitive Negotiations curated by Taiyana Pimentel in 2002 required negotiating permission to tear down the walls of an office of the Consulate General of Mexico in Miami – where the exhibition took place – with the Mexican Minister of Foreign Affairs. As to what we would change, it is very difficult to answer to that; perhaps we probably have a fairly healthy relationship with our past, we try not to punish ourselves for our mistakes or whatever we could have done differently.

Tercerunquinto, “Integration of the Consulate General of Mexico in Miami to the Exhibition”

MEXICO: SENSITIVE NEGOTIATIONS, 2002.

Photo documentation of the action at the Consulate General of Mexico, Miami.

Courtesy of the artists and Proyectos Monclova, Mexico City.

NT: The physical dimensions of your works can drastically shift, from small gestures to monumental interventions; yet, the metaphysical dimension of your work seems to align, would you agree? Could you talk about two projects diametrically different in terms of physical dimensions but similar in terms of their metaphysical dimension?

Tercerunquinto: Dismantling and Relocation of the National Emblem (2008) possesses a very complex monumentality since, beside its size, this emblem – together with the Mexican national anthem and flag – is jealously guarded by the army. As you can imagine, the negotiations we had to go through to complete this work were huge. However, the fact that we were dealing with the Tlatelolco University Cultural Center – whose building is the former headquarters of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs but now part of UNAM – facilitated our work and made it achievable. Still, to avoid controversies, the official justification for the removal of the six marble slabs that make the emblem was the need for restoration, rather than to create a work of art. We accepted such a compromise in order to succeed in our desire to challenge such a loaded site, one that has strong connection to the massacre of students in 1968.

Tercerunquinto: Dismantling and Relocation of the National Emblem (2008) possesses a very complex monumentality since, beside its size, this emblem – together with the Mexican national anthem and flag – is jealously guarded by the army. As you can imagine, the negotiations we had to go through to complete this work were huge. However, the fact that we were dealing with the Tlatelolco University Cultural Center – whose building is the former headquarters of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs but now part of UNAM – facilitated our work and made it achievable. Still, to avoid controversies, the official justification for the removal of the six marble slabs that make the emblem was the need for restoration, rather than to create a work of art. We accepted such a compromise in order to succeed in our desire to challenge such a loaded site, one that has strong connection to the massacre of students in 1968.

Tercerunquinto, “Dismantling and Relocation of the National Emblem”, 2008.

Photo documentation of the action on the façade of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs’ former building, Mexico City

Courtesy of the artists and Proyectos Monclova, Mexico City.

.

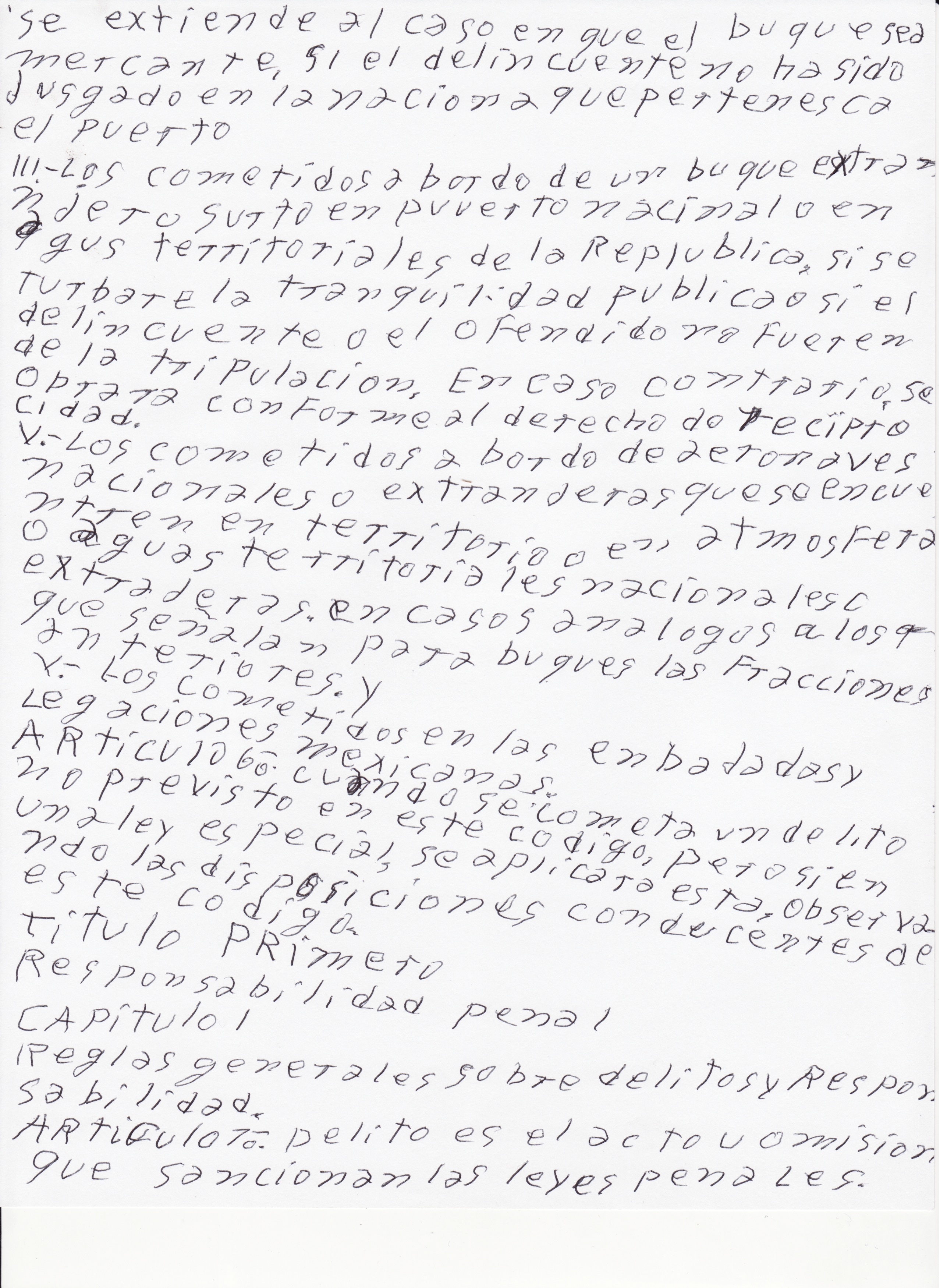

On the other hand, the production of Manual Transcription of the Federal District’s Penal Code of 1967 (2011) required an intimate relationship with a prisoner who, produced a single edition handmade book, which we then decided to donate to the General Archive of the Nation, which is actually located on the site of the former prison of Lecumberri, a place where he had spent the first years of his sentence. In our view, both these projects broach tremendous failings of the Mexican State.

Tercerunquinto, “Manual Transcription of the Federal District’s Penal Code of 1967”, 2011.

Manual transcription made by an inmate in the Santa Martha Acatitla prison, variable dimensions (depends of the space to install every single sheet).

Courtesy of the artists and Proyectos Monclova, Mexico City.

NT: Murals are often associated with Mexican art and its visual culture; your works often employ walls, either as conceptual installations or surfaces for murals, cutouts, etc. Can you elaborate on this connection?

Tercerunquinto: This connection was not there in 2000 when we first discussed the idea of producing Restoration of a Mural Painting (2009-16). At that time, we had not integrated the condition that this work should be done by professional restorers and conservators dealing with artistic heritage; they were a series of street pictorial gestures: we would repaint some political campaign paintings – ‘consigned’ to the public space – which we found on our road trips or in the city itself. At that time there was political and social upheaval, to the extent that we began to seriously think of the likelihood of a change of regime, after having been governed by the same party for seventy years.

The connection you mention took place ten years later. By that time we had already decided that the restoration work should be carried out by a professional restoration team. We had already come up with the idea of confronting the great Mexican artistic legacy of Muralism with the ideas of this project. In addition, when we were asked to produce the project and exhibit it in the old house of David Alfaro Siqueiros, converted at the time into the Sala de Arte Público Siqueiros, we saw very fortunate and pertinent circumstances allowing us to discuss two different conceptions of Muralism. We do not rule out the fact that this was a provocation. All this said, we are interested in walls probably because they are used to insert many desires and failed projects in the public space: those that come from commercial and political advertising as well as the artistic legacy of Muralism. They are documents and themselves constitute an interesting kind of national archive.

Tercerunquinto: This connection was not there in 2000 when we first discussed the idea of producing Restoration of a Mural Painting (2009-16). At that time, we had not integrated the condition that this work should be done by professional restorers and conservators dealing with artistic heritage; they were a series of street pictorial gestures: we would repaint some political campaign paintings – ‘consigned’ to the public space – which we found on our road trips or in the city itself. At that time there was political and social upheaval, to the extent that we began to seriously think of the likelihood of a change of regime, after having been governed by the same party for seventy years.

The connection you mention took place ten years later. By that time we had already decided that the restoration work should be carried out by a professional restoration team. We had already come up with the idea of confronting the great Mexican artistic legacy of Muralism with the ideas of this project. In addition, when we were asked to produce the project and exhibit it in the old house of David Alfaro Siqueiros, converted at the time into the Sala de Arte Público Siqueiros, we saw very fortunate and pertinent circumstances allowing us to discuss two different conceptions of Muralism. We do not rule out the fact that this was a provocation. All this said, we are interested in walls probably because they are used to insert many desires and failed projects in the public space: those that come from commercial and political advertising as well as the artistic legacy of Muralism. They are documents and themselves constitute an interesting kind of national archive.

Tercerunquinto, “Restoration of a Mural Painting”, 2009-2016.

Photo documentation of the action at San Andres Cacaloapan, Puebla (Mexico).

Courtesy of the artists and Proyectos Monclova, Mexico City.

NT: Some of your works, like Public Sculpture in the Urban Periphery of Monterrey, appropriate the language of Land Art, especially how photography has been used to document works, for example with European artists such as Richard Long or Hamish Fulton. Would you agree? Was such a contradiction of terms – Land Art being related to nature, to the outside – a purposeful decision?

Tercerunquinto: It is interesting how from the beginning there were various readings of this work in the light of ideas that came from Minimal and Land Art, or those of Relational Aesthetics. Honestly, although we had always been interested in minimalist sculptural practices, they did not determine our process of work. It was something simpler: taking as a point of departure the basic idea in the “figure-background” drawing, we wanted to move it to the more complex level of “sculpture-context.” Thereby we introduced a fundamental element as a sign of urbanism (and probably of urbanity) such as concrete, in a context that lacked the basic public services such as paved roads, lighting, etc. There, where nobody is concerned about art (why should they be?) we decided to develop our ideas on art, specifically on public sculpture.

Tercerunquinto: It is interesting how from the beginning there were various readings of this work in the light of ideas that came from Minimal and Land Art, or those of Relational Aesthetics. Honestly, although we had always been interested in minimalist sculptural practices, they did not determine our process of work. It was something simpler: taking as a point of departure the basic idea in the “figure-background” drawing, we wanted to move it to the more complex level of “sculpture-context.” Thereby we introduced a fundamental element as a sign of urbanism (and probably of urbanity) such as concrete, in a context that lacked the basic public services such as paved roads, lighting, etc. There, where nobody is concerned about art (why should they be?) we decided to develop our ideas on art, specifically on public sculpture.

Tercerunquinto, “Public sculpture on the urban periphery of Monterrey”, 2003-2006.

Photo documentation of an intervention in a peripheral neighborhood of Monterrey (Mexico).

Courtesy of the artists and Proyectos Monclova, Mexico City.

NT: Can you speak of your work Vendedor de flores (2014)? Is it connected to the work of Mexican artist and muralist Diego Rivera, who made a painting of a female flower vendor [Vendedora de flores, 1949]?

Tercerunquinto: This is a strange coincidence. We never had Diego Rivera in mind when we were discussing the ideas; in fact we kind of laughed when we became aware of the coincidence! Moreover, and far from wanting to create controversy, we must clarify that the folkloric character in Rivera’s painting could not be further away from the ideas we were working on in our project. Our aim is to illustrate the possible distances that exist between a cultural institution – a museum, a gallery, an art center – the cultural, political and economic power they retain and their respective audience. The activation of these agents (a museum, a collection, and a street flower vendor) in Bochum was meant to generate discussions about how distances can vary depending on the audience. This is what is traditionally referred to as institutional critique, which we adopted and twisted into “institutional negotiation.”

Tercerunquinto: This is a strange coincidence. We never had Diego Rivera in mind when we were discussing the ideas; in fact we kind of laughed when we became aware of the coincidence! Moreover, and far from wanting to create controversy, we must clarify that the folkloric character in Rivera’s painting could not be further away from the ideas we were working on in our project. Our aim is to illustrate the possible distances that exist between a cultural institution – a museum, a gallery, an art center – the cultural, political and economic power they retain and their respective audience. The activation of these agents (a museum, a collection, and a street flower vendor) in Bochum was meant to generate discussions about how distances can vary depending on the audience. This is what is traditionally referred to as institutional critique, which we adopted and twisted into “institutional negotiation.”

Tercerunquinto, “Vendedor de flores”, 2014.

Photo documentation of the action at Kunstmuseum Bochum (Germany), Museo Amparo, Puebla (Mexico) and CCA Tel Aviv-Yafo.

Courtesy of the artists and Proyectos Monclova, Mexico City.

NT: You are represented by two galleries, one in Mexico City, Proyectos Monclova, and one in Zurich, Galerie Peter Kilchmann. Although Kilchmann is truly connected to Latin America and specifically Mexico, one cannot think of two more different places than Mexico and Switzerland. Have you ever presented the same work in both galleries? What were the respective reactions? More generally speaking, how do you see your work being translated (or misunderstood) according to the culture and language of the place in which it is displayed?

Tercerunquinto: A very interesting and punctual question. It has happened that the same work has been exhibited in both galleries. We have noticed the difference in perspectives especially when we exhibit a work produced in Mexico that contains ideas and reflections from a Mexican context. It is interesting how, after about forty years of globalization, during which art has served as a cutting-edge mechanism to bridge boundaries, one still perceives such different reactions from showing the same work in two contexts as different as you mention. It seems that in reality some of us have globalized more than others! That’s why, considering the fact that globalization has been a profitable project for some, and a devastating one for others, people are already talking about a post-globalization era.

Tercerunquinto: A very interesting and punctual question. It has happened that the same work has been exhibited in both galleries. We have noticed the difference in perspectives especially when we exhibit a work produced in Mexico that contains ideas and reflections from a Mexican context. It is interesting how, after about forty years of globalization, during which art has served as a cutting-edge mechanism to bridge boundaries, one still perceives such different reactions from showing the same work in two contexts as different as you mention. It seems that in reality some of us have globalized more than others! That’s why, considering the fact that globalization has been a profitable project for some, and a devastating one for others, people are already talking about a post-globalization era.

Courtesy of the artists and Proyectos Monclova.

Photo credit: DOS estudio (Rodrigo Viñas / Patrick López Jaimes).

Tercerunquinto, “Historia Breve de la Construcción”, 2022.

Cinder blocks, bricks and clay blocks, installation view at Centro Cultural Juan Beckmann Gallardo, Santiago de Tequila (Mexico).

Courtesy of the artists and Proyectos Monclova, Mexico City.

NT: Can you talk about the role documents play in your practice?

Tercerunquinto: The way we document our work has had several phases. Originally, during our first four or five years, we were basically interested in doing sculptural-architectural interventions on site, in which we actively participated. We would take some photographs, some videos and then this material would go to some boxes of files; sometimes we would print some photos, although without any clear vision. Then, when we started to be invited to exhibit documentation of these early works, this topic became a matter of discussion. The first few times we did it very literally, showing a series of images that seemed more like pieces of evidence, with the aim to register something we had done. Then we realized that this method was leaving out the much richer and more abstract ideas of our work. We therefore moved to a new phase of documentation where it no longer had anything to do with the original site where the work had happened. It had other potentialities and most importantly, it made us realize the difference between “people” and “audience.” When we work on site, outside of the institution, we don’t think about audiences, but about people; an important epistemic difference.

NT: Do you consider exhibition making, as a form and format, an essential aspect of the way you work, beyond sculpture, beyond installation, beyond site-specific intervention? Taking from that, what is the most appropriate site for your practice to materialize?

Tercerunquinto: We love all the complexity that can be built between these concepts that you mention. With the passing of time we have realized that all the tensions with historical concepts of art, conceptual, institutional, contemporary, intellectual, commercial and so on, have helped us to reach clarity, realizing that our work has been precisely to think, exist and survive in the midst of these tensions.

Tercerunquinto: The way we document our work has had several phases. Originally, during our first four or five years, we were basically interested in doing sculptural-architectural interventions on site, in which we actively participated. We would take some photographs, some videos and then this material would go to some boxes of files; sometimes we would print some photos, although without any clear vision. Then, when we started to be invited to exhibit documentation of these early works, this topic became a matter of discussion. The first few times we did it very literally, showing a series of images that seemed more like pieces of evidence, with the aim to register something we had done. Then we realized that this method was leaving out the much richer and more abstract ideas of our work. We therefore moved to a new phase of documentation where it no longer had anything to do with the original site where the work had happened. It had other potentialities and most importantly, it made us realize the difference between “people” and “audience.” When we work on site, outside of the institution, we don’t think about audiences, but about people; an important epistemic difference.

NT: Do you consider exhibition making, as a form and format, an essential aspect of the way you work, beyond sculpture, beyond installation, beyond site-specific intervention? Taking from that, what is the most appropriate site for your practice to materialize?

Tercerunquinto: We love all the complexity that can be built between these concepts that you mention. With the passing of time we have realized that all the tensions with historical concepts of art, conceptual, institutional, contemporary, intellectual, commercial and so on, have helped us to reach clarity, realizing that our work has been precisely to think, exist and survive in the midst of these tensions.

Tercerunquinto, “Alphabet”, 2023.

Digital images, variable dimensions.

Courtesy of the artists and Proyectos Monclova, Mexico City.

NT: Can you share what you have been working on recently, and any future projects?

Tercerunquinto: We are currently working on a series of artworks for an exhibition in Tequila, Jalisco, where we will also present a box design for the Reserva de la Familia 2023 edition of the company José Cuervo. The exhibition, entitled “Landscape: Figure and Abstraction,” has to do with the notion of landscape. While avoiding a romanticized view of Tequila, we are focused on how technological modernity has caused changes in the landscape, and are continuing to use our “materials”: concrete, mortar and other types of building materials.

In addition, we are working on two new series related to the dynamics of public spaces that were lost during the pandemic. We are surveying, through photography, the kind of monuments that have been subjected to political scrutiny in the last few years. This work does not have a title yet. Furthermore, echoing our work Gramática de la tristeza (2017), we are going back to appropriation of graffiti with the idea of creating a new work called Alphabet, a new typeface featuring a collection of letters from text anonymously written on walls. A prototype design is ready, although we are sure that this is not the end, considering the huge amount of material we have.

Tercerunquinto: We are currently working on a series of artworks for an exhibition in Tequila, Jalisco, where we will also present a box design for the Reserva de la Familia 2023 edition of the company José Cuervo. The exhibition, entitled “Landscape: Figure and Abstraction,” has to do with the notion of landscape. While avoiding a romanticized view of Tequila, we are focused on how technological modernity has caused changes in the landscape, and are continuing to use our “materials”: concrete, mortar and other types of building materials.

In addition, we are working on two new series related to the dynamics of public spaces that were lost during the pandemic. We are surveying, through photography, the kind of monuments that have been subjected to political scrutiny in the last few years. This work does not have a title yet. Furthermore, echoing our work Gramática de la tristeza (2017), we are going back to appropriation of graffiti with the idea of creating a new work called Alphabet, a new typeface featuring a collection of letters from text anonymously written on walls. A prototype design is ready, although we are sure that this is not the end, considering the huge amount of material we have.