Nicola Trezzi: You come from a family deeply involved in art and culture, and you are an architect and principal of the eponymous, acclaimed firm specializing in the restoration of historical homes. Can you describe the moment in your life when you realized you were a collector and that collecting contemporary art would become a pivotal aspect of both your personal and professional life?

Luca Bombassei: It is difficult to identify a precise moment. I started thirty years ago with photography, perhaps because it is more accessible and immediate for those unfamiliar with collecting. My first purchase was an almost monochromatic landscape—a minimal image of a piece of architecture set against a snowy backdrop. What struck me the most was the dialogue between nature and architecture, a theme I still recognize in myself today. Since then, I’ve realized that collecting is a source of inexhaustible stimulation, both in my private life and profession. Art opens many doors to worlds I had not previously considered or known. This continuous discovery fosters a deep fascination with knowledge—one that grows and, in a certain way, sustains itself. Each new encounter, artist, and gallery offers fresh insights into the field of art, which I deeply cherish and from which new choices continually emerge.

Luca Bombassei.

Photo credit: ©Jacopo Salvi.

Photo credit: ©Jacopo Salvi.

Luca Bombassei’s journey into collecting does not begin with a single, fixed origin, yet one image lingers in memory—a seemingly simple photograph of architecture set against a snowy backdrop. This early acquisition, minimal yet profound, resonates with a quiet clarity that continues to shape his sensibility as a collector. The dialogue between nature and architecture remains a central thread, weaving through a collection existing at a nexus of time and reflecting Bombassei’s deep engagement with contemporary Italian art and design. From this snowy backdrop, a collection has bloomed, spanning media from sculpture to glass, and unfolding across residences in Venice, Milan, and Salento. In this interview with Nicola Trezzi for ZETTAI, Bombassei reflects on his approach to collecting, the role of intuition in decision-making, and the evolution of his practice over time.

Olivier Mosset, Wallpainting per Gallipoli, 2018.

Polyurethane enamel, 13 x 5 m ca.

Photo credit: ©Andrea Ferrari.

Polyurethane enamel, 13 x 5 m ca.

Photo credit: ©Andrea Ferrari.

NT: Name an artist, an artwork, and an exhibition that have informed the way you look at and collect art.

LB: More than specific names, I would like to highlight an exhibition that was a breakthrough for me and shaped my way of seeing (and collecting) contemporary art: the 1999 Venice Biennale, titled dAPERTutto and curated by Harald Szeemann. It was a particularly important year for the Biennale, as it definitively established the display model by which international exhibitions alongside national pavilions continue to be defined. That year, the Golden Lion Award for Best National Pavilion was given to five female Italian artists: Monica Bonvicini, Luisa Lambri, Bruna Esposito, Paola Pivi, and Grazia Toderi. Over the following years, these artists—undoubtedly among the finest in Italy—have entered my collection, with one or more works by each of them.

LB: More than specific names, I would like to highlight an exhibition that was a breakthrough for me and shaped my way of seeing (and collecting) contemporary art: the 1999 Venice Biennale, titled dAPERTutto and curated by Harald Szeemann. It was a particularly important year for the Biennale, as it definitively established the display model by which international exhibitions alongside national pavilions continue to be defined. That year, the Golden Lion Award for Best National Pavilion was given to five female Italian artists: Monica Bonvicini, Luisa Lambri, Bruna Esposito, Paola Pivi, and Grazia Toderi. Over the following years, these artists—undoubtedly among the finest in Italy—have entered my collection, with one or more works by each of them.

Left to right

On the wall: Roni Horn, Isabelle and Marie, 2005. Two standard C-prints on Fuji Crystal Archive, mounted on 1/8’’ Sintra, 46.99 × 39.34 cm / 48.4 × 40.2 × 2.5 cm each (framed).

Stokke Chair, 1970s.

Monica Bonvicini, Latent Combustion #5, 2015. Chainsaws, black polyurethane (matte finish), chains, hooks, 275 × 130 × 130 cm.

Lucio Fontana, Concetto Spaziale, Attese, 1965. Waterpaint on blue canvas, 65 × 55 cm.

Carlo Scarpa, Easel, 1950–55. Iroko, patinated steel, brass, 261 cm (height).

On the table: Vanessa Beecroft, White Ceramic Head, 2015. Ceramic, 35.5 × 20 × 26.7 cm.

Photo credit: ©Andrea Ferrari.

On the wall: Roni Horn, Isabelle and Marie, 2005. Two standard C-prints on Fuji Crystal Archive, mounted on 1/8’’ Sintra, 46.99 × 39.34 cm / 48.4 × 40.2 × 2.5 cm each (framed).

Stokke Chair, 1970s.

Monica Bonvicini, Latent Combustion #5, 2015. Chainsaws, black polyurethane (matte finish), chains, hooks, 275 × 130 × 130 cm.

Lucio Fontana, Concetto Spaziale, Attese, 1965. Waterpaint on blue canvas, 65 × 55 cm.

Carlo Scarpa, Easel, 1950–55. Iroko, patinated steel, brass, 261 cm (height).

On the table: Vanessa Beecroft, White Ceramic Head, 2015. Ceramic, 35.5 × 20 × 26.7 cm.

Photo credit: ©Andrea Ferrari.

NT: Are you an impulsive buyer or someone who likes to take his time to reflect? Is there a work you regret not having bought?

LB: I am impulsive. Although I admire those who collect in a scientific way, I do so in a more instinctive manner, based on the attraction I feel either toward a given artwork or for the story and experience that the artist wants to communicate.

NT: Do you prefer to buy from Italian galleries or foreign galleries? Do you value an intimate relationship with the people selling art to you, or do you prefer to keep a certain distance?

LB: In line with the variety of works I collect, the places from which I acquire them are quite heterogeneous—from mid-sized Italian galleries and antiquarians, with whom I have developed mutual feelings of affection and appreciation over the years, to more institutional galleries and major auction houses. I do not choose one type of relationship over another a priori; my decisions are guided by the artwork I fall in love with and by whether the circumstances feel right for a purchase.

LB: I am impulsive. Although I admire those who collect in a scientific way, I do so in a more instinctive manner, based on the attraction I feel either toward a given artwork or for the story and experience that the artist wants to communicate.

NT: Do you prefer to buy from Italian galleries or foreign galleries? Do you value an intimate relationship with the people selling art to you, or do you prefer to keep a certain distance?

LB: In line with the variety of works I collect, the places from which I acquire them are quite heterogeneous—from mid-sized Italian galleries and antiquarians, with whom I have developed mutual feelings of affection and appreciation over the years, to more institutional galleries and major auction houses. I do not choose one type of relationship over another a priori; my decisions are guided by the artwork I fall in love with and by whether the circumstances feel right for a purchase.

Sol LeWitt, Untitled (from the “Splotches” series),

Black fiberglass,

152.4 × 121.9 × 101.6 cm.

Black fiberglass,

152.4 × 121.9 × 101.6 cm.

NT: While your collection is truly international, you still actively support Italian artists. What do you think makes Italian art unique? Who are the young talents you are currently following, both in Italy and abroad?

LB: As much as it might sound obvious, I believe that Italian art—including the most contemporary—is unique due to the extraordinary artistic and cultural legacy our history carries. This means an inevitable dialogue with the past, being conscious and explicit—such as in Francesco Vezzoli’s reading of classical art—or limited to the artistic education that represents the preliminary stage of the production of new works. If we approach this historical richness with virtuosity, rather than reducing it to a sterile act of recuperation, Italy’s cultural legacy will reveal itself as an irreplaceable resource that ought to be cherished. This dialogue with the future is something that has always guided my decisions, as an architect, collector, and so on.

Regarding young artists, in recent years I have taken an interest in contemporary African art, particularly from countries whose stories have yet to be told and whose voices are still emerging within academic and cultural discourse. Additionally, I have developed a particular interest in female artists—among them Lucia Veronesi, a Mantua-born artist based in Venice, whose recent itinerant project La desinenza estinta (The Extinguished Desinence) I was pleased to support.

LB: As much as it might sound obvious, I believe that Italian art—including the most contemporary—is unique due to the extraordinary artistic and cultural legacy our history carries. This means an inevitable dialogue with the past, being conscious and explicit—such as in Francesco Vezzoli’s reading of classical art—or limited to the artistic education that represents the preliminary stage of the production of new works. If we approach this historical richness with virtuosity, rather than reducing it to a sterile act of recuperation, Italy’s cultural legacy will reveal itself as an irreplaceable resource that ought to be cherished. This dialogue with the future is something that has always guided my decisions, as an architect, collector, and so on.

Regarding young artists, in recent years I have taken an interest in contemporary African art, particularly from countries whose stories have yet to be told and whose voices are still emerging within academic and cultural discourse. Additionally, I have developed a particular interest in female artists—among them Lucia Veronesi, a Mantua-born artist based in Venice, whose recent itinerant project La desinenza estinta (The Extinguished Desinence) I was pleased to support.

Paola Pivi, Why am I so worried?, 2016,

Urethane foam, plastic, feathers, 72 x 221 x 107 cm.

Reproduction from Vanessa Beecroft, Performance VB84, Sala di Niobe, Galleria degli Uffizi, Firenze

Lithographic print, 64 × 44 cm, Arti Grafiche Parini, Torino.

Photo credit: ©Andrea Ferrari.

Urethane foam, plastic, feathers, 72 x 221 x 107 cm.

Reproduction from Vanessa Beecroft, Performance VB84, Sala di Niobe, Galleria degli Uffizi, Firenze

Lithographic print, 64 × 44 cm, Arti Grafiche Parini, Torino.

Photo credit: ©Andrea Ferrari.

NT: Design and architecture are very important to you. Your passion for Memphis is well known, and I was wondering which other designers resonate with you. Do you buy art with a specific design piece in mind, considering how various pieces might complement each other, and so on?

LB: For a few years, alongside my art collection, I have acquired design pieces made of glass. I find glass to be a material that holds particular significance, as it has allowed many designers to engage with and come close to art. In this sense, I see it as the link between two strands of my collecting pursuits—art and design. My collection ranges from Scarpa to Sottsass, following, in some ways, my main point of reference in design, though still oriented toward the production of glass works.

LB: For a few years, alongside my art collection, I have acquired design pieces made of glass. I find glass to be a material that holds particular significance, as it has allowed many designers to engage with and come close to art. In this sense, I see it as the link between two strands of my collecting pursuits—art and design. My collection ranges from Scarpa to Sottsass, following, in some ways, my main point of reference in design, though still oriented toward the production of glass works.

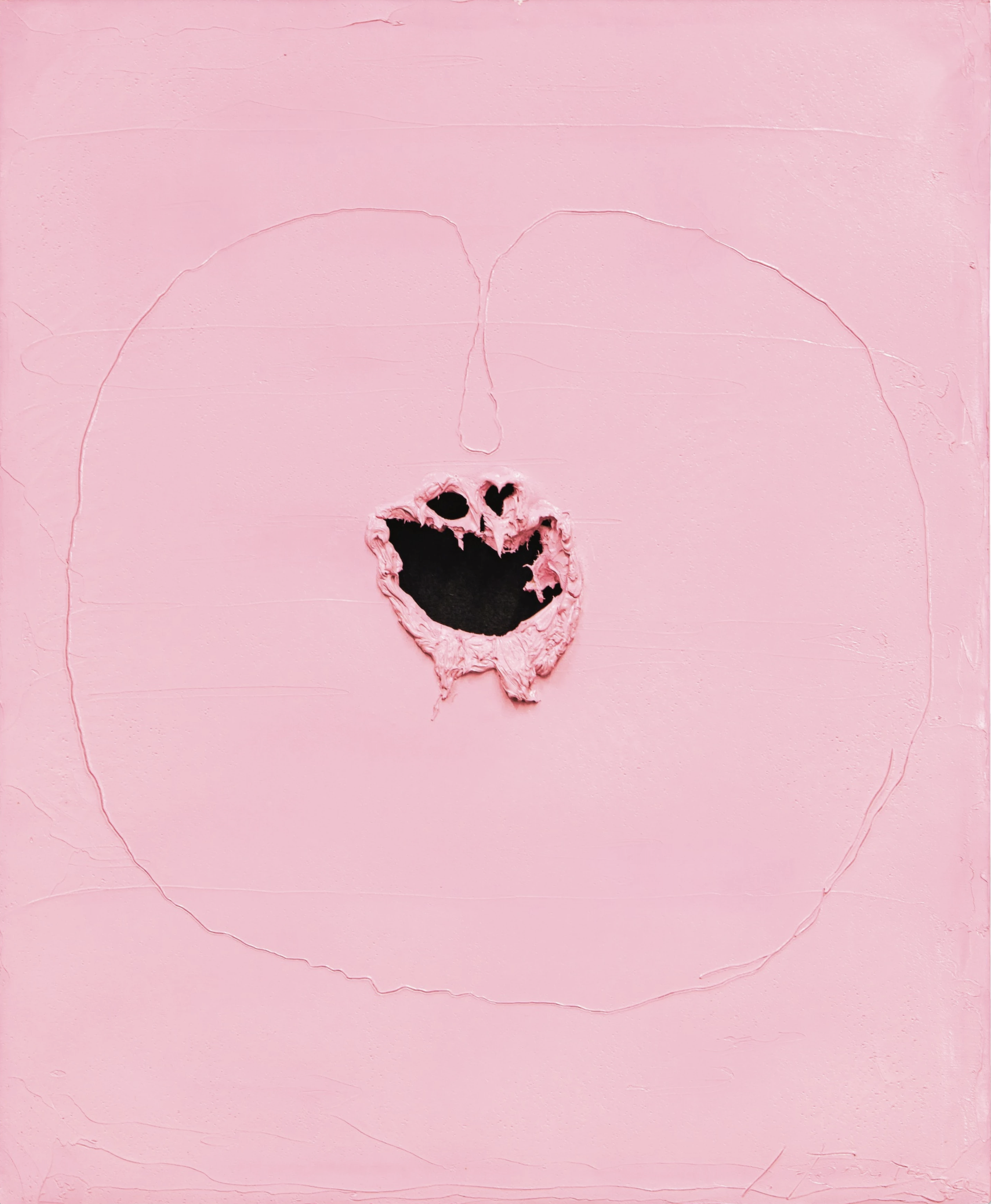

Lucio Fontana, Concetto spaziale, 1966,

Oil on canvas,

73,6 x 60,3 cm.

Photo credit: ©Jacopo Salvi.

Oil on canvas,

73,6 x 60,3 cm.

Photo credit: ©Jacopo Salvi.

NT: As a collector, you pay great attention to how your collection is displayed at home. You divide your time between Milan, Venice, and Salento in Puglia, in the south of Italy—each home is different yet still reflects your personality. Can you associate each home with a different facet of your personality and mention a work of art that encapsulates it?

LB: I would begin with my home in Venice, which best represents the virtuous blend of historicism and contemporaneity so characteristically unique to this city. Among the historical works I have chosen to place there, the most significant is undoubtedly a Capriccio by Canaletto, which happily coexists with pieces by Barbara Kruger and Jenny Holzer, among others. Though seemingly distant, there is a decipherable thread between the ways they engage with society. Just as Canaletto embedded messages of social critique in his works, Kruger and Holzer do the same—only more directly.

In my Milanese apartment, Italian designs from the ’50s and ’60s, like those by Sottsass, are mixed with bold pieces featuring strong colors by Andy Warhol and John Giorno. Finally, in my masseria in Salento, I would highlight a piece by Ibrahim Mahama—a large work created with jute bags that are well integrated into the spacious areas and the original architecture of the house, which I am particularly fond of.

LB: I would begin with my home in Venice, which best represents the virtuous blend of historicism and contemporaneity so characteristically unique to this city. Among the historical works I have chosen to place there, the most significant is undoubtedly a Capriccio by Canaletto, which happily coexists with pieces by Barbara Kruger and Jenny Holzer, among others. Though seemingly distant, there is a decipherable thread between the ways they engage with society. Just as Canaletto embedded messages of social critique in his works, Kruger and Holzer do the same—only more directly.

In my Milanese apartment, Italian designs from the ’50s and ’60s, like those by Sottsass, are mixed with bold pieces featuring strong colors by Andy Warhol and John Giorno. Finally, in my masseria in Salento, I would highlight a piece by Ibrahim Mahama—a large work created with jute bags that are well integrated into the spacious areas and the original architecture of the house, which I am particularly fond of.

Roni Horn, Isabelle and Marie, 2005,

Two standard C-prints on Fuji Crystal Archive,

mounted on 1/8’’ Sintra,

46.99 × 39.34 cm / 48.4 × 40.2 × 2.5 cm.

NT: Speaking of Venice, you have been deeply involved in the city’s cultural scene: you were President of the Venice International Foundation, dedicated to safeguarding its artistic heritage, and you are also involved in the London-based film production company Hoffman, Barney & Foscari. Given all of this, I’m sure the Venice Film Festival is an unmissable event for you—let alone the Venice Biennale! Tell us about your love affair with the city.

LB: Venice has always played a central role in my life, partly due to the Venetian roots of my family. It is a city that inspires love and, for me, an inexhaustible source of inspiration—precisely because of its extraordinary historical heritage and contemporary landscape, especially when considering the future of art and culture. We therefore return to the fundamental idea of reconciling historical legacies with future-oriented visions. Venice not only embodies all of this but also possesses a unique ability to evolve—meaning it can transform and look ahead while remaining loyal to its past, always with an international outlook, always moving forward. My four-year tenure as President of the Venice International Foundation has just ended, and it was an exceptional way to strengthen my connection to the city and highlight the importance of preservation in shaping future cultural decisions. I was pleased to conclude my mandate with the extraordinary exhibition of Francesco Vezzoli in the Scarpa-designed rooms of the Museo Correr.

Through this perspective, the vitality of the Biennale—whether in visual art, cinema, architecture, or dance—serves as a fundamental reality check for me, reinforcing the identity of a city that continuously evolves through an ongoing dialogue between tradition and innovation.

LB: Venice has always played a central role in my life, partly due to the Venetian roots of my family. It is a city that inspires love and, for me, an inexhaustible source of inspiration—precisely because of its extraordinary historical heritage and contemporary landscape, especially when considering the future of art and culture. We therefore return to the fundamental idea of reconciling historical legacies with future-oriented visions. Venice not only embodies all of this but also possesses a unique ability to evolve—meaning it can transform and look ahead while remaining loyal to its past, always with an international outlook, always moving forward. My four-year tenure as President of the Venice International Foundation has just ended, and it was an exceptional way to strengthen my connection to the city and highlight the importance of preservation in shaping future cultural decisions. I was pleased to conclude my mandate with the extraordinary exhibition of Francesco Vezzoli in the Scarpa-designed rooms of the Museo Correr.

Through this perspective, the vitality of the Biennale—whether in visual art, cinema, architecture, or dance—serves as a fundamental reality check for me, reinforcing the identity of a city that continuously evolves through an ongoing dialogue between tradition and innovation.

Francesco Vezzoli, La Musa dell’Archeologia piange, 2021.

Roman Marble Togatus (Circa late 2nd-1st Century), bronze,

140 x 36 x 35 cm.

Photo credit: ©Jacopo Salvi.

NT: Now Milan: Since the 2015 Expo, the city seems to have left its gray and austere reputation behind, emerging as an international European capital whose lively atmosphere attracts not only those drawn to design or fashion week but also those seeking a base to live and work. What makes Milan so unique? Do you think its plurality of voices, its individualism, and its ambition—so perfectly embodied by its constellation of institutions and galleries—are its true strength? And, aside from the much-anticipated museum of contemporary art, what do you think the city still lacks?

LB: Although it is widely criticized today, Milan—like anything that is developing and opening new avenues—remains a city with a certain dynamism and a plethora of opportunities unmatched elsewhere in Italy. The sheer breadth of its cultural offerings, the plurality of voices in its artistic scene, and the social and professional possibilities it fosters make it a city full of promise—one that continues to attract people from both within Italy and abroad.

LB: Although it is widely criticized today, Milan—like anything that is developing and opening new avenues—remains a city with a certain dynamism and a plethora of opportunities unmatched elsewhere in Italy. The sheer breadth of its cultural offerings, the plurality of voices in its artistic scene, and the social and professional possibilities it fosters make it a city full of promise—one that continues to attract people from both within Italy and abroad.

Francesco Vezzoli, Disco Pompidou (Carol Bouquet), 2018. Inkjet print on canvas, metallic embroidery, 68 x 46 cm.

Davina Semo, Glow, 2019. Acrylic mirror, plywood, ball bearings, hardware, stainless steel 184,15 x 123,19 cm.

On the table in the background, couple of marble statuettes.

Photo credit: ©Andrea Ferrari.

NT: My last question to you is about guidance. Your collection is very personal, yet I imagine you rely on the advice of people you trust and appreciate. Who do you turn to? With whom do you have your deepest, most meaningful conversations about art? And, in turn, what kind of advice would you give to a young collector about to embark on this journey—this wonderful adventure—into the world of collecting contemporary art?

LB: Without a doubt, I enjoy exchanging ideas with people I trust and appreciate. I like to listen to their opinions and attend art fairs in their company. There are Italian curators and artists I truly admire, with whom, over the years, I have built special bonds that go beyond mere professional relationships. With them, I also share convivial gatherings, and we converse at length about art and culture. That said, no matter what advice I gratefully and lovingly receive, when it comes to choosing, I follow only my mind—and, above all, my heart.

LB: Without a doubt, I enjoy exchanging ideas with people I trust and appreciate. I like to listen to their opinions and attend art fairs in their company. There are Italian curators and artists I truly admire, with whom, over the years, I have built special bonds that go beyond mere professional relationships. With them, I also share convivial gatherings, and we converse at length about art and culture. That said, no matter what advice I gratefully and lovingly receive, when it comes to choosing, I follow only my mind—and, above all, my heart.

On the wall: John Baldessari, Intersection Series: Woman on bed and man under bed / Beach Scene, 2002. Acrylic and spray paint on photo print, 114.3 × 214.5 cm.

On the table (white marble coffee table by Angelo Mangiarotti):

Fratelli Campana, Prototype Sculpture for Venini.

Enzo Mari, two green glass cubes.

Ettore Sottsass, black ceramic vase, Y29 Yantra Series, Design Centre, 1969.

Photo credit: ©Andrea Ferrari.