Nicola Trezzi: Please describe your collection, including how you would define it, and whether its formation follows a systematic approach or emerges from a more personal, instinctive perspective.

Wiyu Wahono: I follow a simple notion: good artwork reflects the spirit of the time. I ask simple questions: when and why was “contemporary” art born? What was it that annoyed these young artists for them to start acting discursively, to move away from mainstream art? I read a variety of books: Arthur C. Danto, Terry Smith, Julian Stallabrass, and others. And it is in drawing from these cumulative sources of knowledge that I systematically build my contemporary art collection.

Artworks grappling with themes of identity politics, oppression, Western hegemony, urbanization, digitalization, and the environment inform the diverse range of media that I collect: photography, scanography, video art (digital moving image), video mapping, installation, performance art, sound art (pure sound), light art, bio art, robotic art, science and technological art, paintings and sculptures, among others. I also collect immaterial art.

Having spent two decades in Germany before returning to Indonesia, Wiyu Wahono brings a global lens to Southeast Asia’s art scene, where he continues to challenge the very nature of collecting. In this interview with Nicola Trezzi for ZETTAI, Wahono delves into his ways of seeing and acquiring art, the allure of works at the intersection between art and technology, and his independence from both the market and institutional systems when it comes to what to buy and where to buy.

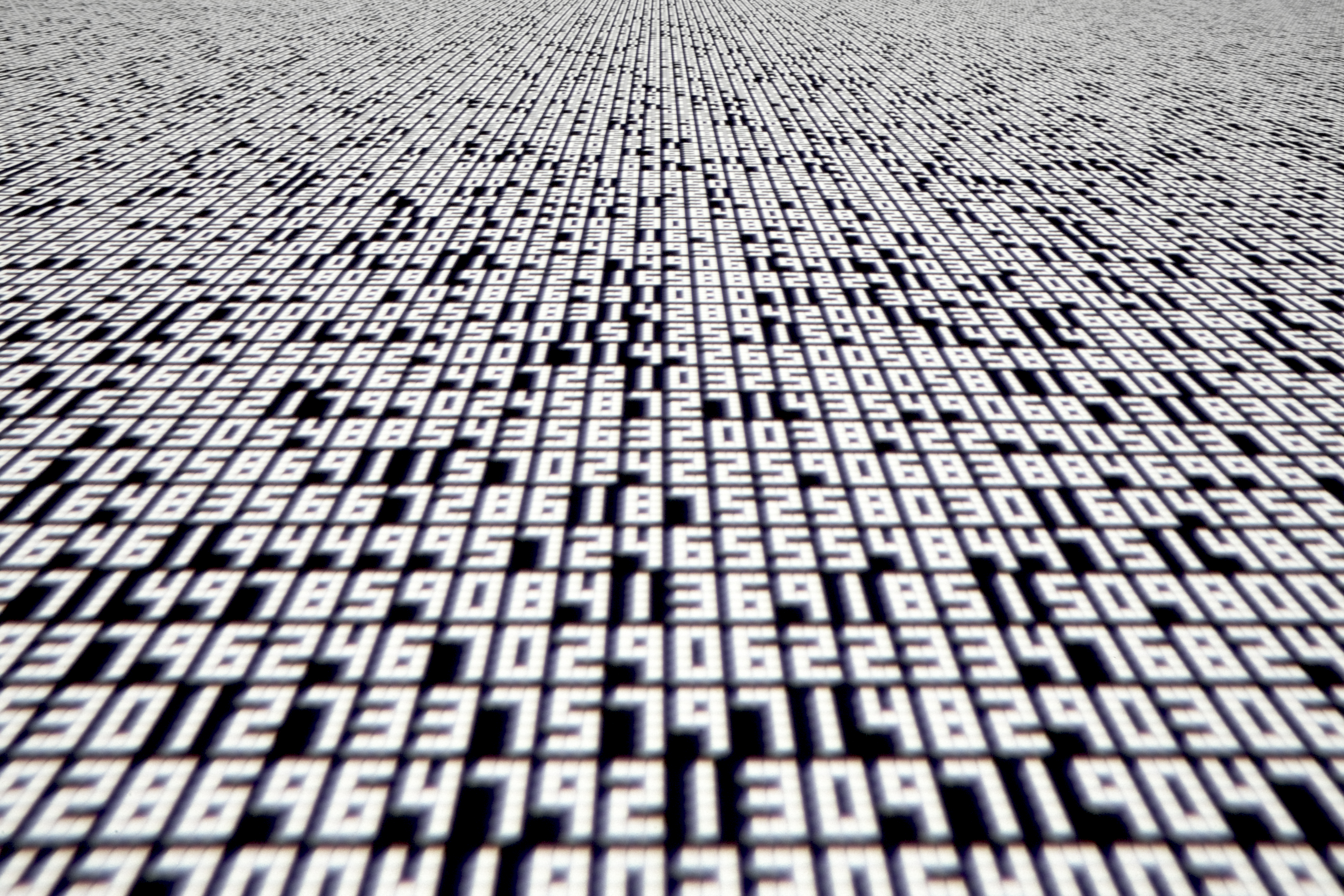

Ryoji Ikeda, data.tron, 2007, audiovisual installation.

Photo credit: Ryuichi Maruo.

Courtesy of Yamaguchi Center for Arts and Media.

Photo credit: Ryuichi Maruo.

Courtesy of Yamaguchi Center for Arts and Media.

NT: You mention works that fall under categories such as video mapping, performance art, sound art, light art, bio art, robotic art, and science and technological art. What challenges do you face as a collector, particularly when it comes to acquiring and maintaining such works?

WW: Collecting such works presents challenges on multiple levels. It starts with understanding the technical specifications required to properly display a piece, such as finding the right multimedia projector to achieve a full, precise image on a wall with predefined dimensions. For an excellent viewing experience, specific projector resolution, brightness (measured in ANSI lumens), throw distance, and lens type are all necessary. Some technological artworks are also temperamental and often difficult to turn on. Computers, for example, don’t always start as expected and may need to be repeatedly shut down and restarted before functioning correctly.

Bio art requires even greater, if not extreme, maintenance, especially when incorporating living organisms. Living Mirror (2013) by Howard Boland and Laura Cinti is an interactive piece consisting of numerous glass flasks filled with liquid and living magnetic bacteria that must be cleaned twice a year. It takes four days for one person to loosen thousands of tiny screws and meticulously wash the insides of all 265 glass flasks.

WW: Collecting such works presents challenges on multiple levels. It starts with understanding the technical specifications required to properly display a piece, such as finding the right multimedia projector to achieve a full, precise image on a wall with predefined dimensions. For an excellent viewing experience, specific projector resolution, brightness (measured in ANSI lumens), throw distance, and lens type are all necessary. Some technological artworks are also temperamental and often difficult to turn on. Computers, for example, don’t always start as expected and may need to be repeatedly shut down and restarted before functioning correctly.

Bio art requires even greater, if not extreme, maintenance, especially when incorporating living organisms. Living Mirror (2013) by Howard Boland and Laura Cinti is an interactive piece consisting of numerous glass flasks filled with liquid and living magnetic bacteria that must be cleaned twice a year. It takes four days for one person to loosen thousands of tiny screws and meticulously wash the insides of all 265 glass flasks.

Ming Wong, Life of Imitation, 2009.

Photo credit: Ming Wong.

Photo credit: Ming Wong.

NT: What was the last artwork you acquired, and what drew you to it?

WW: Melati Suryodarmo’s Eins und Eins (2016) had been on my wish list for years before I recently finally decided to acquire it. A powerful performative piece, it unfolds in an entirely white room, where the artist repeatedly pours black ink into her mouth—vomiting, groaning, and embodying a visceral expression of resistance. It is through this act that she echoes Indonesia’s history, where millions have fought against oppression in its many forms.

NT: Do you prefer to acquire artworks from art fairs or galleries, and what informs your choice? Do you also engage with the secondary market?

WW: I began collecting digital art over 17 years ago, at a time when neither commercial galleries nor art fairs embraced the medium—a reality that persists today, with digital art still occupying a marginal space in the market. More recently, my focus has expanded to science and technology-based art, yet these works remain largely overlooked by galleries and fairs. As such, I typically buy artwork directly from artists.

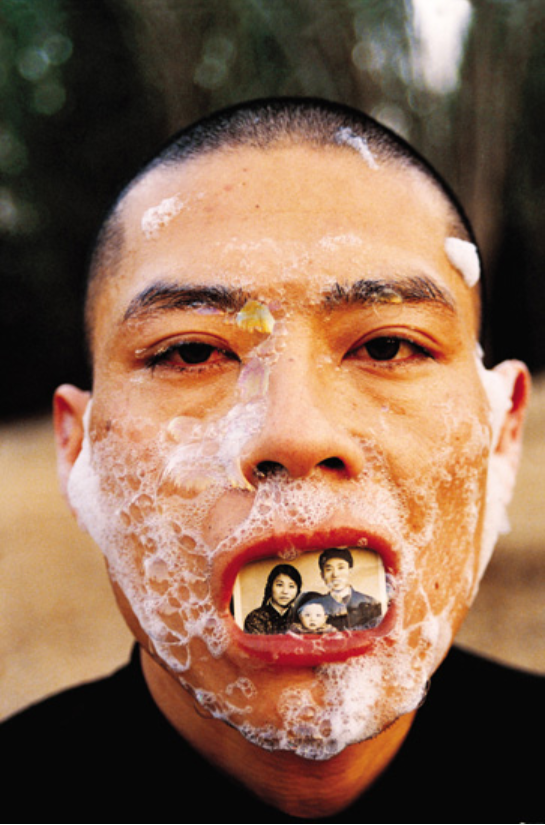

This is not to say, however, that I am opposed to purchasing from galleries, art fairs, or the secondary market. I have acquired works by Zhang Huan and Shirin Neshat through the secondary market, and my purchase of Eins und Eins by Melati Suryodarmo was made through ShanghART.

WW: Melati Suryodarmo’s Eins und Eins (2016) had been on my wish list for years before I recently finally decided to acquire it. A powerful performative piece, it unfolds in an entirely white room, where the artist repeatedly pours black ink into her mouth—vomiting, groaning, and embodying a visceral expression of resistance. It is through this act that she echoes Indonesia’s history, where millions have fought against oppression in its many forms.

NT: Do you prefer to acquire artworks from art fairs or galleries, and what informs your choice? Do you also engage with the secondary market?

WW: I began collecting digital art over 17 years ago, at a time when neither commercial galleries nor art fairs embraced the medium—a reality that persists today, with digital art still occupying a marginal space in the market. More recently, my focus has expanded to science and technology-based art, yet these works remain largely overlooked by galleries and fairs. As such, I typically buy artwork directly from artists.

This is not to say, however, that I am opposed to purchasing from galleries, art fairs, or the secondary market. I have acquired works by Zhang Huan and Shirin Neshat through the secondary market, and my purchase of Eins und Eins by Melati Suryodarmo was made through ShanghART.

Melati Suryodarmo, Eins und Eins, 2016.

Single-channel HD video, stereo sound, 29 minutes 21 seconds.

NT: Do studio visits play a pivotal role in your decision to follow an artist and their work? If so, can you share a studio visit that particularly shaped your perspective as a collector?

WW: I don’t enjoy studio visits, nor do I enjoy being friends with artists. I evaluate artworks based on whether they resonate with and strengthen my existing collection. For me, it’s not about whether the artist has attended a prestigious art school or whether they are destined for “success.” I’m not concerned with their future trajectory or whether they may one day stop creating. If a piece can add depth or coherence to my collection, it becomes part of it.

It also does not matter to me the resale value of the works I acquire. In fact, I consider myself fortunate to have managed to distance myself from the idea of profiting from my collection. The real issue today, in my view, is the growing obsession among collectors with the idea of art as an investment. Too many are driven by the desire for financial gain rather than a genuine passion for the work itself.

WW: I don’t enjoy studio visits, nor do I enjoy being friends with artists. I evaluate artworks based on whether they resonate with and strengthen my existing collection. For me, it’s not about whether the artist has attended a prestigious art school or whether they are destined for “success.” I’m not concerned with their future trajectory or whether they may one day stop creating. If a piece can add depth or coherence to my collection, it becomes part of it.

It also does not matter to me the resale value of the works I acquire. In fact, I consider myself fortunate to have managed to distance myself from the idea of profiting from my collection. The real issue today, in my view, is the growing obsession among collectors with the idea of art as an investment. Too many are driven by the desire for financial gain rather than a genuine passion for the work itself.

Zhang Huan, Foam 13, 1998.

NT: You’ve spent many years living in Europe, and your knowledge of Post-War European and American art is extensive, as well as that of the exhibitions that accompanied said generation of artists. Beyond Harald Szeemann, which curators have inspired and still inspire you, and why?

WW: Okwui Enwezor is very inspiring. The issue of Western hegemony remains a relevant topic today, though I personally think that, most of the time, this issue—along with the need to give balance to underrepresented minorities, in accordance with categories like gender, race, ethnicity, class, and sexuality—often appears in exhibitions in a way that feels quite flat. I don’t believe that simply counting how many women or artists of color are included in exhibitions is enough to spark a meaningful dialogue in art.

I believe curators should develop more sophisticated approaches to enhancing meaningful art production by artists from peripheral positions. One relevant way to do this is by presenting parallel histories, which doesn’t always mean “rewriting history.” For example, bringing a figure like Rasheed Araeen to the forefront.

WW: Okwui Enwezor is very inspiring. The issue of Western hegemony remains a relevant topic today, though I personally think that, most of the time, this issue—along with the need to give balance to underrepresented minorities, in accordance with categories like gender, race, ethnicity, class, and sexuality—often appears in exhibitions in a way that feels quite flat. I don’t believe that simply counting how many women or artists of color are included in exhibitions is enough to spark a meaningful dialogue in art.

I believe curators should develop more sophisticated approaches to enhancing meaningful art production by artists from peripheral positions. One relevant way to do this is by presenting parallel histories, which doesn’t always mean “rewriting history.” For example, bringing a figure like Rasheed Araeen to the forefront.

Deni Ramdani, 0 Degree, 2017.

Soil, water, goldfish.

Soil, water, goldfish.

NT: I would now like to shift the focus to your peers, so to speak: Is there any collector who has inspired or continues to inspire you, and why?

WW: I have read several books about the most prominent art collectors, and at the top of the list is Giuseppe Panza. His ability to acquire works that would later become central pieces in the collections of over ten world-renowned museums, such as the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum in New York and MOCA Los Angeles, is something I find truly extraordinary.

Another collector who stands out is Justin K. Thanhauser, along with his wife, Hilde. Their decision to donate iconic pieces from their collection to the Guggenheim Museum is a perfect example of how a collection can transcend personal ownership to become part of shared cultural heritage. Then there’s Erich Marx, who, through his collection, transformed the Hamburger Bahnhof in Berlin into one of the most important contemporary art spaces in Europe. The German government entrusted him with a former train station to house his collection—an extraordinary gesture that underscores the significance of his vision.

WW: I have read several books about the most prominent art collectors, and at the top of the list is Giuseppe Panza. His ability to acquire works that would later become central pieces in the collections of over ten world-renowned museums, such as the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum in New York and MOCA Los Angeles, is something I find truly extraordinary.

Another collector who stands out is Justin K. Thanhauser, along with his wife, Hilde. Their decision to donate iconic pieces from their collection to the Guggenheim Museum is a perfect example of how a collection can transcend personal ownership to become part of shared cultural heritage. Then there’s Erich Marx, who, through his collection, transformed the Hamburger Bahnhof in Berlin into one of the most important contemporary art spaces in Europe. The German government entrusted him with a former train station to house his collection—an extraordinary gesture that underscores the significance of his vision.

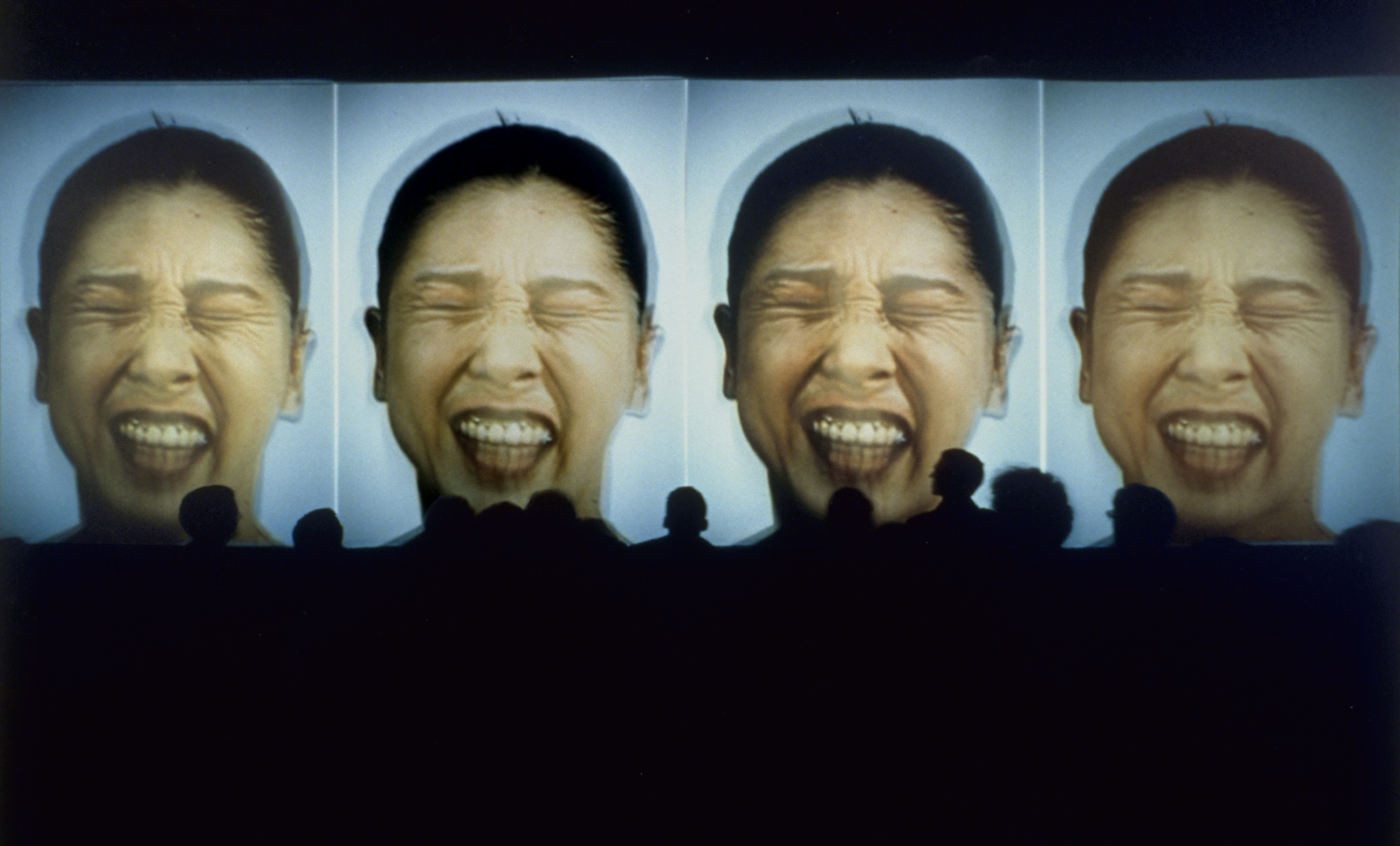

Granular-Synthesis (Kurt Hentschläger and Ulf Langheinrich), Modell 5, 1994.

QT ProRes, 1920 × 1080, 5.1-channel audio installation, 30:00:00.

Photo credit: Bruno Klomfar and Gebhard Sengmüller.

NT: Could you compare the art scenes in Germany, where you lived for many years, and Indonesia, where you reside now? What are the strengths and weaknesses of each, from your perspective?

WW: When I lived in Germany, I wasn’t yet an art collector. While I regularly visited exhibitions for personal enjoyment, I didn’t immerse myself in art theory or the nuances of the art scene at the time. It was more of an appreciation than an intellectual engagement.

However, upon moving to Indonesia and attending exhibitions here, I began to notice a significant shift. The curatorial texts accompanying the exhibitions were often written in a language that felt overly complex, filled with terms that seemed to be more about showcasing the curator's expertise than communicating with a broader audience. As someone who was an art enthusiast but not deeply versed in theory, I found this approach alienating at first.

That said, things have improved over time. There is now a growing generation of young curators in Indonesia who are more approachable and keen on bridging the gap between the art world and the public. They’re moving away from overly academic language and making the art scene more accessible, which is encouraging.

WW: When I lived in Germany, I wasn’t yet an art collector. While I regularly visited exhibitions for personal enjoyment, I didn’t immerse myself in art theory or the nuances of the art scene at the time. It was more of an appreciation than an intellectual engagement.

However, upon moving to Indonesia and attending exhibitions here, I began to notice a significant shift. The curatorial texts accompanying the exhibitions were often written in a language that felt overly complex, filled with terms that seemed to be more about showcasing the curator's expertise than communicating with a broader audience. As someone who was an art enthusiast but not deeply versed in theory, I found this approach alienating at first.

That said, things have improved over time. There is now a growing generation of young curators in Indonesia who are more approachable and keen on bridging the gap between the art world and the public. They’re moving away from overly academic language and making the art scene more accessible, which is encouraging.

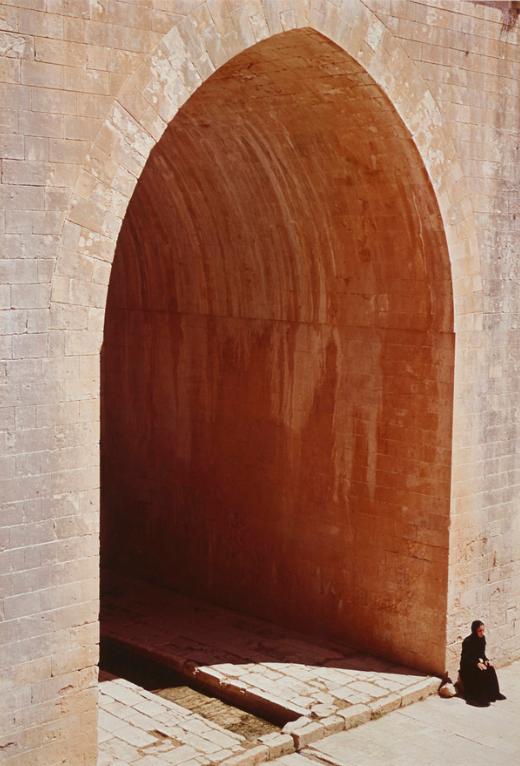

Shirin Neshat,

Untitled (from the Soliloquy Series), 1999.

NT: Some would argue that the Indonesian art scene, while full of energy, lacks the infrastructure seen in more established art markets like South Korea or China. Emerging artists are gaining attention, but the scene has not yet reached the level of international prominence that other countries have achieved. What do you believe the scene needs to advance to the next stage, if anything?

WW: Indonesia, with a population of 285 million, is home to a significant number of art collectors. For an emerging artist doing something intriguing, the local market offers relatively accessible opportunities for success. However, this abundance of collectors can also be a double-edged sword. Many young artists, finding immediate recognition and success, sometimes become complacent, leading to work that feels repetitive or lacks depth. The ease of entry into the market has, in some ways, led to a lack of critical self-reflection among emerging creators.

Another pressing issue is the educational gap. Many Indonesian artists, particularly those from the younger generation, aren’t taught how to articulate their concepts effectively, either in their native language or in English. This deficiency limits their ability to engage in deeper, more meaningful dialogues about their work, which in turn hinders their growth on the international stage. To elevate the scene, I believe the government and local institutions should invest in creating programs that help bring internationally recognized art experts to Indonesia in cities like Yogyakarta, Bandung, or Jakarta. These programs would provide valuable opportunities for dialogue, knowledge exchange, and critical feedback, helping to nurture the next generation of artists and curators while fostering a more robust international presence for Indonesian art.

WW: Indonesia, with a population of 285 million, is home to a significant number of art collectors. For an emerging artist doing something intriguing, the local market offers relatively accessible opportunities for success. However, this abundance of collectors can also be a double-edged sword. Many young artists, finding immediate recognition and success, sometimes become complacent, leading to work that feels repetitive or lacks depth. The ease of entry into the market has, in some ways, led to a lack of critical self-reflection among emerging creators.

Another pressing issue is the educational gap. Many Indonesian artists, particularly those from the younger generation, aren’t taught how to articulate their concepts effectively, either in their native language or in English. This deficiency limits their ability to engage in deeper, more meaningful dialogues about their work, which in turn hinders their growth on the international stage. To elevate the scene, I believe the government and local institutions should invest in creating programs that help bring internationally recognized art experts to Indonesia in cities like Yogyakarta, Bandung, or Jakarta. These programs would provide valuable opportunities for dialogue, knowledge exchange, and critical feedback, helping to nurture the next generation of artists and curators while fostering a more robust international presence for Indonesian art.

Teguh Ostenrik, Domus Anguillae (House of Eel), 2022.

Seabed installation in Desa Sembiran, Tejakula, Buleleng, Bali.

Photo credit: Adi Siagian.

NT: You are known for buying difficult works, including videos, installation, and new media. Are you interested in new developments in this path, such as post-internet art or artificial intelligence? If so, which artists do you find most inspiring in this space?

WW: Ryoji Ikeda, Eduardo Kac, Heather Dewey-Hagborg, Pierre Huyghe, Holly Herndon and Mat Dryhurst, Nathan Thompson and Guy Ben-Ary. I think AI is a revolution—one that I expect to have an even greater impact on visual art than the invention of the photographic camera in the 19th century. I started buying AI art five years ago and am still exploring how this bodiless intelligence, with incomplete sense apparatus, no gender, no age, and no private sphere, will redefine artistic and aesthetic boundaries in a non-human realm. As for post-internet art, I’m not familiar with it.

WW: Ryoji Ikeda, Eduardo Kac, Heather Dewey-Hagborg, Pierre Huyghe, Holly Herndon and Mat Dryhurst, Nathan Thompson and Guy Ben-Ary. I think AI is a revolution—one that I expect to have an even greater impact on visual art than the invention of the photographic camera in the 19th century. I started buying AI art five years ago and am still exploring how this bodiless intelligence, with incomplete sense apparatus, no gender, no age, and no private sphere, will redefine artistic and aesthetic boundaries in a non-human realm. As for post-internet art, I’m not familiar with it.

XHABARA, Dawn of the Dajjal, 2021.

MP4 video, 1 min 23 sec.

NT: You once said that you “want to have artworks made of fire, water, smoke, wind, and more.” Did you find them? Considering that Arte Povera is a bit out of reach these days...

WW: Yes, I’ve been fortunate to acquire works that fit this vision. I purchased a sculpture by Indonesian artist Asmujo Irianto depicting a standing man with a burning fire on his head. Another piece by Julian Abraham Togar consists of distilled water (made from the urine of diabetes patients) in glass bottles, placed inside a refrigerator; this was exhibited at the 2018 Sydney Biennale. I also collected a work by Deni Ramdani, which features a transparent plastic bag filled with water and live fish. This piece won the Bandung Contemporary Art Award (BaCAA) in 2017, and as someone who has served as a juror for BaCAA since its inception 13 years ago, it felt particularly significant.

There are also a couple of pieces I’m still eyeing. One is a smoke artwork by Azusa Murakami and Alexander Groves, currently on display at M+ in Hong Kong. I’m also drawn to a wind piece by Ryan Gander that was part of Documenta 13 in 2012. I would love to add both of these to my collection.

NT: If you could go back and advise your younger self on collecting, what kind of advice would you give him?

WW: Reading contemporary art theory books is an act of refining our taste; refined taste gives us the ability to discover the artistic quality of an artwork. Focus on the artistic quality of artworks, as the coherence of an art collection is important. Focus on a few key themes or directions, as it’s simply impossible to collect all the great works available in the market.

WW: Yes, I’ve been fortunate to acquire works that fit this vision. I purchased a sculpture by Indonesian artist Asmujo Irianto depicting a standing man with a burning fire on his head. Another piece by Julian Abraham Togar consists of distilled water (made from the urine of diabetes patients) in glass bottles, placed inside a refrigerator; this was exhibited at the 2018 Sydney Biennale. I also collected a work by Deni Ramdani, which features a transparent plastic bag filled with water and live fish. This piece won the Bandung Contemporary Art Award (BaCAA) in 2017, and as someone who has served as a juror for BaCAA since its inception 13 years ago, it felt particularly significant.

There are also a couple of pieces I’m still eyeing. One is a smoke artwork by Azusa Murakami and Alexander Groves, currently on display at M+ in Hong Kong. I’m also drawn to a wind piece by Ryan Gander that was part of Documenta 13 in 2012. I would love to add both of these to my collection.

NT: If you could go back and advise your younger self on collecting, what kind of advice would you give him?

WW: Reading contemporary art theory books is an act of refining our taste; refined taste gives us the ability to discover the artistic quality of an artwork. Focus on the artistic quality of artworks, as the coherence of an art collection is important. Focus on a few key themes or directions, as it’s simply impossible to collect all the great works available in the market.